An authentic edition of Aesop may not be what you recall from children’s versions. But while it may not contain easy to digest morals, it makes up for with a sense of history, period, humour and wide-spread influence.

I would not be surprised if a large proportion of people had heard of at least one of Aesop’s fables. And I would be willing to guess which one was the most familiar to them. The fable of the tortoise and the hare seems especially enduring, perhaps due to the agreeability of its moral.

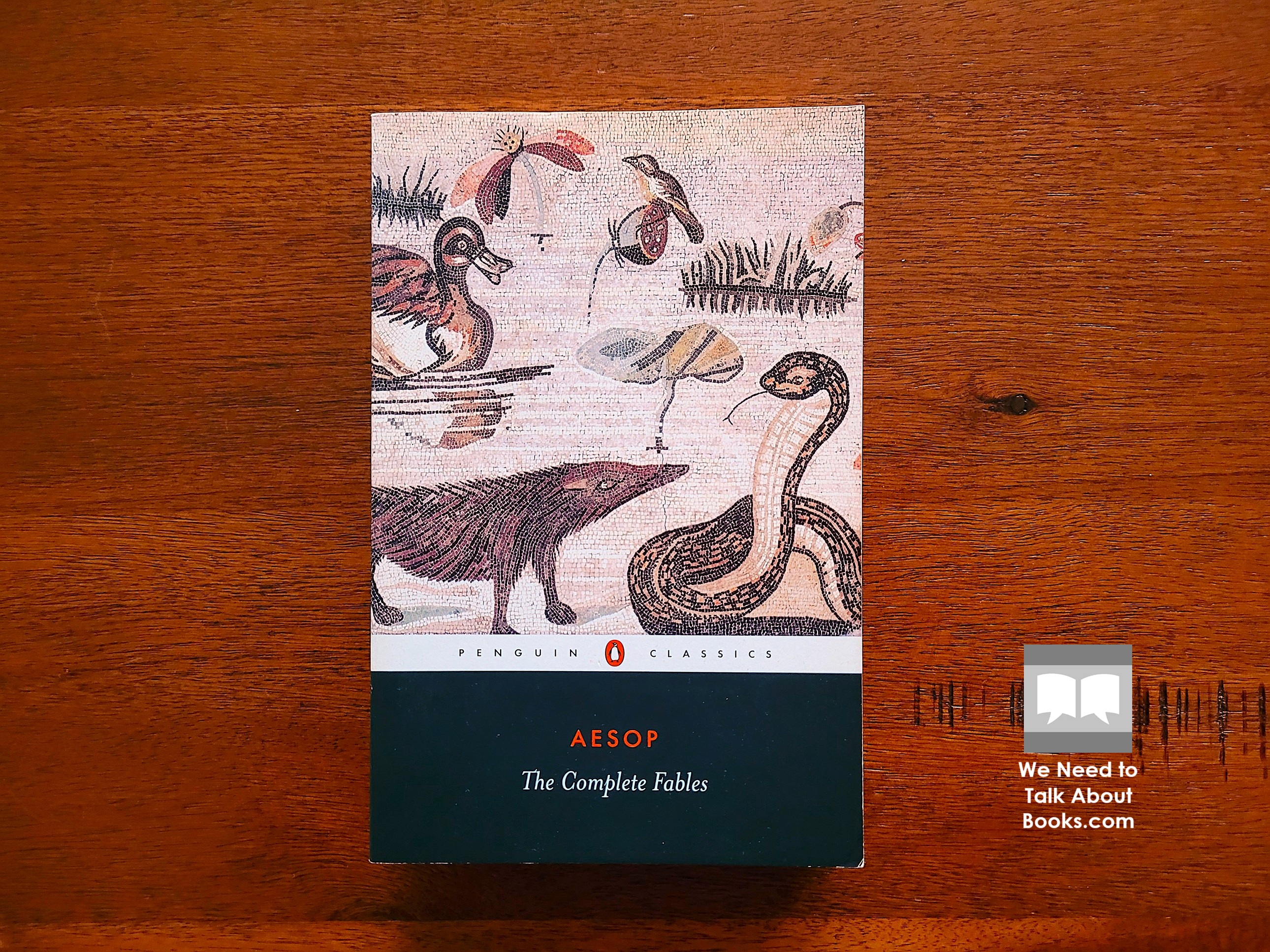

Although, in this Penguin Classics edition of The Complete Fables of Aesop, I had to wait until the fable numbered 352 before encountering the tortoise and the hare. And it had a different moral to the one I am familiar with. I grew up with the moral to the story being that ‘slow and steady wins the race’. But this edition has an alternative, and perhaps better, one of ‘hard work often prevails over natural talent if they are neglected’.

As it turns out, the fables of Aesop we are familiar with, most likely via a children’s book, are adapted versions from the Victorian period with associated morals as well. Many are not even Aesop originals – if such a thing can even be determined.

It seems likely that Aesop was a real person who lived in the early sixth century BCE. He seems to have been enslaved probably after being captured in war, and subsequently worked as a secretary and lawyer. He also seems to have been something of a wit and a humourist, inventing and collecting fables to make his points.

The Oxen and the Axle

Some oxen were pulling a cart. As the axle creaked, they turned round and said to it:

‘Hey, friend! We are the ones who carry all the burden and yet it is you who moans!’

Thus, one sees people who make out that they are exhausted, when it is others who have gone to the trouble.

Aristophanes uses Aesop in his plays. Socrates and Plato also seem to be aware of him. Aristotle seems to have been a great appreciator of him and may have collected and systematised his fables. He also tells a story of Aesop using a fable during a court case. But it was Demetrius of Phalerum, a pupil of Aristotle’s colleague Theophrastus, whose collection of Aesop survived and became the standard version, without which Aesop may have been lost to us.

Determining which fables are authentically from Aesop is a difficult endeavour. It seems clear that works from other ancient writers and regions have been incorporated into Aesop. The most obvious clue is that the fables contain several animals – cats, lions, camels, elephants, monkeys, apes – which are alien to ancient Greece.

The fables have also travelled across cultural boundaries. Some, for example, appear in ancient Indian texts. It is not always possible to determine which way the stories travelled and which was the original source. Though the editors of this edition suggest that from what we know from other examples, it seems more likely the stories in common with India travelled to India. One fable – The Logs and the Olive – even seems to have found its way into the Bible. The author of the Book of Judges seems to have mistranslated and missed the joke of the original.

Other hints at authenticity can come from the use of Greek mythological elements and the vocabulary. Both can be used to decide which fables have an earlier origin and are more likely to be authentic to Aesop.

This 1998 edition is based on the Chambrey 1927 text. As far as the editors are aware, it is the first ‘complete’ edition of Aesop’s fables in English. Though there are many more fables attributed to Aesop that are not in this edition, authenticating these others remains too difficult, while many in this collection are dubiously attributed to Aesop for the reasons above.

Another interesting factor in understanding the fables is that some clearly belong together in a set. Some are contrary to nature. For example, there are several fables involving an ass and a lion who become friends and go hunting together. It would have been obvious to ancient listeners that asses are not carnivores and a pairing with a lion is unlikely. A possible explanation is that these fables are part of a set and the ass and the lion represent real historical persons being satirised. Their identity is lost to us but may have been known to their original audience for their amusement.

The Kid on the Roof of the House, and the Wolf

A kid who had wandered on to the roof of a house saw a wolf pass by and he began to insult and jeer at it. The wolf replied:

‘Hey, you there! It’s not you who mock me but the place on which you are standing.’

This fable shows that often it is the place and the occasion which give one the daring to defy the powerful.

But otherwise, the attributes of the plants and animals used in the fables is important to the point being made. The editors have therefore made a great effort to ensure the translation correctly identifies them. Another thing I am grateful to the editors for is that they have not sanitised or excluded material that might be offensive to modern readers.

Thus, one must not become blinded by pride when one is enriched by shameful means, especially when one is of low birth and without beauty.

As you may imagine, many of the morals of these stories have not stood the test of time. They come from a period where slavery, racism, sexism and homophobia was common and unchallenged. While these parts may make me cringe, I am grateful to know that this is a reaction the editors have left for me to make and have otherwise allowed me to experience the material as an ancient would hear it or as near as possible. Again, it is worth remembering that the moralistic interpretation is something later editors applied to Aesop. The original is perhaps better understood as jokes and satire rather than wisdom.

[…] the fables are not the pretty purveyors of Victorian morals that we have been led to believe. They are instead savage, course, brutal, lacking in all mercy or compassion, and lacking also in any political system other than absolute monarchy.

[…]

This is largely a world of brutal, heartless men – and of cunning, of wickedness, of murder, of treachery and deceit, of laughter at the misfortune of others, of mockery and contempt. It is also a world of savage humour, of deft wit, of clever word play, of one-upmanship, of ‘I told you so!’

From the Introduction

This does mean that reading this version may not be as satisfying as the sanitised, moralised Victorian one we are perhaps all more familiar with. Reading Aesop did make me wonder what it is about fables that make them appealing. I think there has always been great appeal for succinct words of wisdom to live by. Memento Mori (‘Remember You Must Die’) and Temet Nosce (‘Know Thyself’) being two of my personal favourites.

For this reason, I have an interest in one day reading Confucius and possibly the Ionian philosophers. The appeal and impact of fables, aphorisms, proverbs and epigrams has gone far beyond ancient philosophers and religious texts. They live on in corporate slogans, tweets and memes. Andrew Hui has a book – A Theory of the Aphorism; From Confucius to Twitter – that may help explain the appeal.

The Peacock and the Crane

The Peacock was making fun of the crane and criticising his colour:

‘I am dressed in gold and purple,’ he said. ‘You wear nothing beautiful on your wings.’

‘But I,’ replied the crane, ‘sing near to the stars and I mount up to the heights of heaven. You, like the cockerels, can only mount the hens down below.’

It would be better to be renowned and in poor garments than to live without honour in rich attire

I think that for readers interested in Aesop, this Penguin Classics edition is the one to read. It is as ‘complete’ and ‘authentic’ as is reasonably possible. The care that has been made with the translation and annotation is impressive. And the Introduction by Robert Temple aids readers appreciate Aesop for what it is and what it is not. Whatever our sensitive twenty-first century ears may make of Aesop, the fables’ influence on our language and literature is undeniable. We should remember this whenever we use terms that have the origin in the fables such as ‘sour grapes’ and ‘swan song’.

Thanks for this most interesting post. I used to do a library unit of work on Aesop with Preps (5-year-olds) and they were really good for getting discussion going about moral complexities. The stories are obviously short, to suit the short attention span of little kids, but with well illustrated picture books, there was more to the story. For example, the story of the Golden Goose is not just a fable about greed, if the children’s attention was drawn to the shabbiness of clothing and the tumbledown shack in the picture, and why they might have been so desperate to get more and more…

And then I would ask, would it make any difference to their opinion if the house had been a grand palace and the clothes were elegant and expensive…

So then we could consider why the illustrator who obviously wasn’t there in Ancient Greece to know, chose to draw the characters that way!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. I had not fully appreciated just how much can be packed into a short fable. Being so short and deceptively simple, they sound like ideal tools for teaching the foundations of literature. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ooh, you’ve inspired me! Think Aesop needs to go on my reading list…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much!

LikeLike