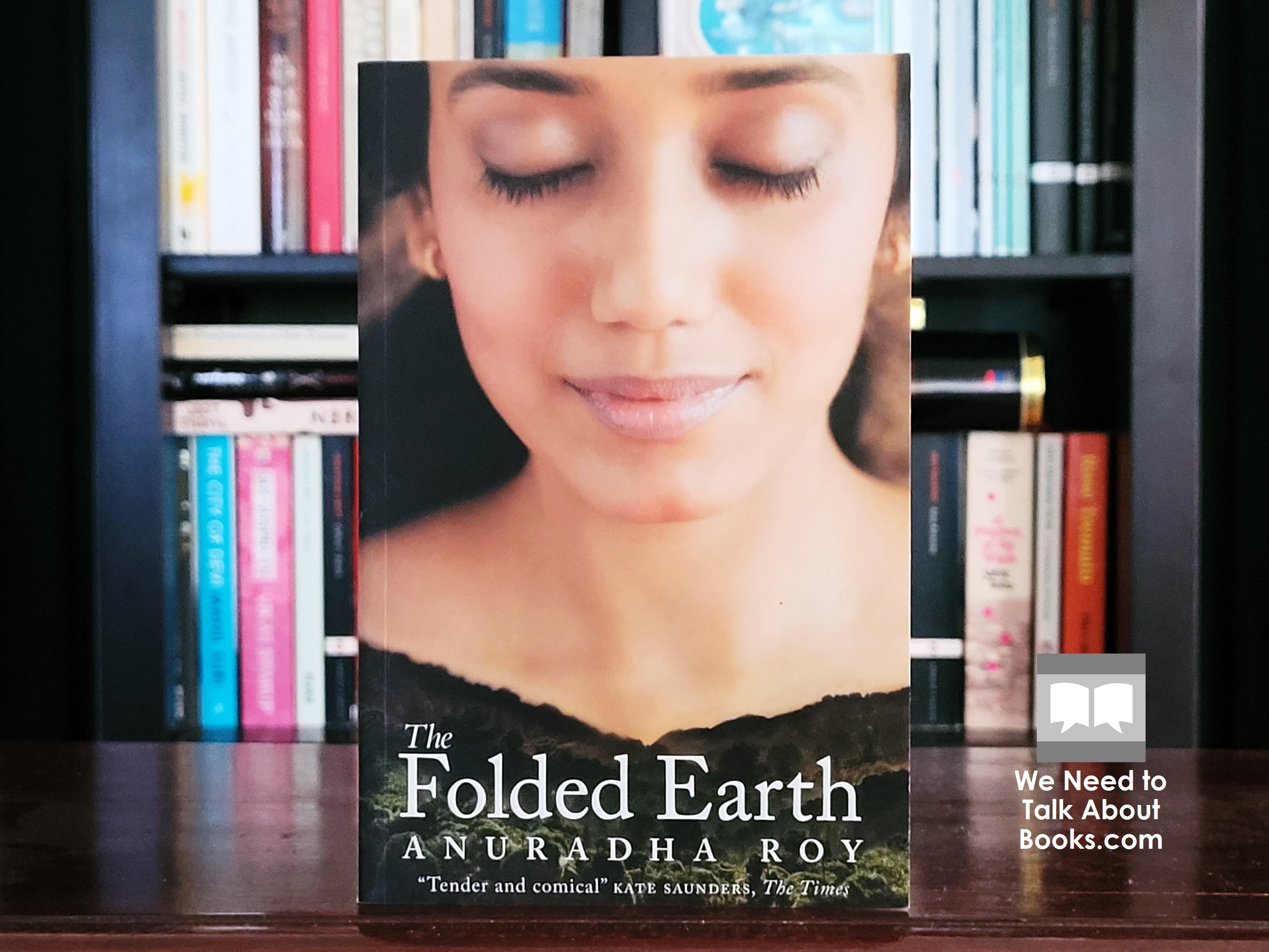

Anuradha Roy’s The Folded Earth is a short novel of tragedy, loss and grief. Yet the world viewed through protagonist Maya’s eyes, of life in an isolated small town, with its strong characters and open secrets, is a world readers will enjoy visiting.

In the foothills on the Indian side of the Himalayas is the small town of Ranikhet. An army town, the townspeople wake in the mornings to the sound of bugle calls and pass generals walking their dogs when doing their errands. Smallholding farmers walk their few cattle through thick forests and narrow gorges to sparse areas for grazing. As well as the small businesses providing essentials there is a Christian Mission school and a few large estates.

One of the newer residents of the town is Maya. A young woman, Maya moved to the isolated town where she has no friends or family following a devastating tragedy.

Against the wishes of her family, Maya married Michael, a press photographer. Belonging to a different religion, Maya’s family would not accept Michael and Maya chose love over her family. Her choice broke her parent’s hearts but neither side seem ready to reconcile. Besides, Maya had no reason to doubt her choice being the happiest she had ever been.

But Maya’s and Michael’s happiness did not last. A keen trekker, Michael frequently embarked on trips away to fulfill his hobby. His last trip was to trek to Roopkund. An ambitious climb for an amateur, it was a trip he did not return from. When his body was found it was suspected that Michael had broken his ankle before being caught in a snowstorm from which he did not stand a chance.

I was alone. I had no contact with friends: I had lost them over the years of being wrapped up in Michael. I had in effect no family although my parents did live in the same city. My father had made a great show of formerly disowning me when I married. A son-in-law of a different religion was abhorrent. My mother was too intimidated by him to do more than steal out for occasional trysts with me at a temple. She had no way of getting news to me unless I contacted her. I did not. Not yet. What was I to say to her? The pain would extinguish her. I had a job, but it did not cross my mind that I needed to inform my office why I had stopped coming to work. A tin with ashes lay in my bed where Michael should have been. I was twenty-five years old and already my life was over.

Devastated by grief, Maya has moved the town of Ranikhet, the stage from which climbs to Roopkund are made and where Michael is buried in the local Christian cemetery.

Maya lives in a small cottage on the grounds of a large estate. Living in the estate’s mansion is Diwan Sahib. Before Independence, Diwan had been Finance Minister to the Nawab of Surajgarh. Though he lives alone, Diwan has frequent visitors. Many of them are scholars researching Surajgarh and the Nawab and come to hear Diwan’s anecdotes. But most have an ulterior motive. It is known that the Mountbatten’s and Nehru visited Surajgarh during Diwan’s time there and it is rumoured that Edwina Mountbatten and Nehru exchanged notes during their stay. To the frustration of his visitors, Diwan won’t confirm whether he has any of the notes in his possession or any knowledge of their contents.

Though unqualified, Maya works as a teacher at the local Christian school. The school also operates a jam factory. The factory provides funding for the school and work for the students and Maya has been asked to help run the enterprise. Given that her estranged family own a successfully chutney business it was expected that Maya would have some useful expertise. But Maya has no head for accounts. She is even less successful as a teacher.

Living in a neighbouring cottage on Diwan’s land is Charu, one of Maya’s failing students. A dreamy teenage girl, Charu lives with Ama, her stern authoritative grandmother, and her brother who has a mental disability. With her neighbours; Charu’s family and friends, Diwan and his visitors, Maya feels she has all the family she needs.

Years go by with very little change to the small mountain town but change there is on the horizon. Politicians try to spur enthusiasm by making a target of the Christian school. The lifestyles of Charu’s family are not appreciated by those who want to make Ranikhet a destination for tourists. And re-entering Diwan’s life is Veer. Apparently a distant relative, Veer works as a guide for foreign and domestic visitors making treks. Though Diwan welcomes his return, it upends Diwan’s life in disturbing ways and Maya can’t be sure if Veer’s presence is good for Diwan or for her.

The Folded Earth is a short novel of simple charm and it is easy to see why. The first source is its location. There is the romance of mountain country; of rolling hills, thick forests, deep and narrow valleys, snow and water and the footpaths through them. It is an appeal for which I am an easy mark.

Michael’s yearnings made me understand how it is that some people have the mountains in them while some have the sea. The ocean exerts an inexorable pull over sea-people wherever they are – in a bright-lit, inland city or the dead centre of a desert – and when they feel the tug there is no choice but somehow to reach it and stand in its immense, earth-dissolving edge, straight away calmed. Hill-people, even if they’re born in flatlands, cannot be parted for long from the mountains. Anywhere else is exile. Anywhere else, the ground is too flat, the air too dense, the trees too broad-leaved for beauty. The colour of the light is all wrong, the sounds nothing but noise.

The second is that this is a small-town novel. Alongside the main plot there are more anecdotes than subplots. There is a familial closeness between all the characters and a sense that secrets cannot remain hidden here for long. And typical of the small-town novel are the eccentric supporting characters who provide the story with much of its colour and the reader with much of their enthusiasm. Ama, Charu’s grandmother, is a good example of this and provided much of my enjoyment of this novel.

Our town has a private history that is revealed only to those who live here, by those who have lived here longer. Ama had a daily story for me both about the dead and the living, talking in the same breath of Janaki on the next hill who made bhang and charas out of the marijuana plants that grew wild all over the hillsides, and of unmarried Missis Lily who had fallen pregnant forty years ago by the judge of the local court. When I went to the Christian cemetery, where I had buried Michael’s ashes, I recognised the names on the tombstones from stories I had been told over the years. In the older part of the graveyard was Charlie Darling beneath a gravestone with winged angels. He had been dead since 1912, of syphilis, I had been told, after too many visits to Lal Kurti, where pretty Kumaoni women earned extra money from soldiers stationed in Ranikhet’s army barracks. The fiery Angelina was a few feet away, beneath a marble slab with carved roses. She never came out of anaesthesia after some minor surgery at the hospital. The general, now in his 90s, had been mourning her for decades. He came to her grave every week with Bozo, and if we met there, he gave me a ride home in his old ambassador. […] He held himself as high as his 5 remaining feet would allow and as he drove he alternated between humming songs from old Hollywood musicals and holding forth on the anarchy of the country. “It’s going to the dogs,” he would say and immediately apologised to Bozo: “not you, dear boy, not you. You would rule with an iron paw.”

A theme of the novel is the battle between youth and tradition, between the future and the past, which takes place on several fronts. In a society where traditionalism dominates, difficult decisions will not be uncommon. It is in Maya’s choice of her love of Michael over her family. Maya also plays witness to a similar choice faced by Charu. It is also a decision the town faces in its local election.

Complicating the battle is the work of the town planner. He is unsympathetic towards tradition and enthusiastic for economic progress but his disdain for traditional lifestyles and needs of the townspeople is cruel. Veer too seems eager to have the past shuffle off but his methods and motivations are clouded.

The Folded Earth is a novel more of mood than plot. It is above all a story of grief. Central of course is Maya’s grief for Michael. As the years go by it is clear to see that Maya’s move to Ranikhet is not a new beginning, the making of a new life, but an extended period of limbo.

I would not look into the future. My life had been too cruelly overturned once before for me to think of anything but the present moment. I would negotiate each day as if I were riding a leaf in a flowing stream: enough to stay afloat. I would not ask for more.

Her work, whether at the school, the factory or helping Diwan with his pet retirement project, is completely unfulfilling. She makes no attempt to try to move forward with her life and neglects opportunities to do so. Of course, the reason she moved to Ranikhet in the first place was not to help her move on with her life but to be closer to Michael in death.

Two of his shirts hung in the cupboard unwashed. I had made him leave them that way so that I could bury my face in them to breathe in his smell while waiting for him to return. The new camera bag his office had given him for assignments lay on the bottom shelf of the cupboard, unused.

It had taken me all these years to claw my way back from that day to some kind of normality.

I had lost my taste for adventure, my impulsiveness. I wished Veer had never come, to fling a stone into my calm pond.

Contrasting this dire mood and tragic course of the main plot, Charu’s story reminds the reader that to live a life means to take risks, breach horizons and challenge traditions. It is the way Maya herself used to live and, the reader hopes, will find the strength to live again.

I cannot say I found The Folded Earth a riveting or profound read. As I have said, it is not that sort of novel. It will find resonance with those readers who appreciate the romance of small towns beneath mountains, of eccentric older characters, young folly and frustration for change. It is a short moody novel about tragedy and grief and the superhuman effort to overcome it.

My hunch about continuations is that they ought to be planned: You ought to attempt to compose a set of three first or if nothing else sketch out a set of three assuming that you have any confidence in your film.

LikeLike

Hi Kenneth, was this comment meant for a different post?

LikeLike