The Woodlanders is possibly one of the lesser Hardy novels. But that does not mean it contains any less of Hardy’s trademark of exploring the tragic consequences of making bad choices in love.

Late at night, George Melbury, a timber merchant, is outside his house pacing back-and-forth, lost in troubling thoughts. Years ago, Melbury married a young woman, though, as far as he is concerned, he seduced her away from her true love; a man named Winterborne. Melbury has carried the guilt of these events ever since. He soon had a daughter, Grace, but his wife died in childbirth and Melbury has since remarried. Winterborne also married and had a son, Giles, but Winterborne has since died. Melbury vowed to himself that he will right his previous wrongs by seeing his daughter marry the son of Winterborne.

As the years have gone by, however, the situations of the Melbury’s and the Winterborne’s have changed. The families live in the small village of Little Hintock, surrounded by woodland. Melbury’s timber business has grown over the years and he enjoys a certain level of wealth and independence. Eager to give his daughter an education and experience beyond their isolated existence; Melbury has sent Grace to an exclusive boarding school.

Giles Winterborne, meanwhile has made his own way as an honest workman. He tends the local apple orchards to make cider and can also be counted on by Melbury to supervise the workmen for his timber business. But now that Grace can enjoy an inheritance, has an education and has developed a taste for culture above her humble rural origins, Melbury has begun to wonder if Giles may no longer be good enough for his daughter.

It is hardly the line of life for a girl like Grace, after what she’s been accustomed to. I didn’t foresee that, in sending her to boarding-school, and letting her travel, and what not, to make her a good bargain for Giles, I should really be spoiling her for him. Ah ‘tis a thousand pities! But he ought to have her – he ought!

Though Giles never believed he had any right to Grace, his affection for her is true but he can sense that he may lose his dream of marrying her.

Nevertheless, he had her father’s permission to win her if he could; and to this end it became desirable to bring matters soon to a crisis. If she should think herself too good for him, he must let her go, and make the best of his loss. The question was how to quicken events towards an issue.

When Grace returns to Little Hintock, Giles embarks on a last ditch attempt to win her affection and her father’s respect with a Christmas party, but his failure only confirms Melbury’s doubts about Giles.

A kindly pity of his household management, which Winterborne saw in her eyes whenever he caught them, depressed him much more than her contempt would have done.

But what other options are there for Grace in a such an isolated village?

As it happens, Mrs Charmond, a wealthy widow who occupies a local estate, has shown an interest in the company of Grace. Melbury hopes that through Mrs Charmond Grace may enjoy the refinements she has been accustomed to while away at school. Mrs Charmond may also introduce Grace to higher society if she takes Grace with her on her frequent trips to the continent.

There is also the prospect of a new doctor, Edred Fitzpiers, who has set up a practice in the area. Keeping mostly to himself, Fitzpiers is a mysterious presence in the small village. Locals find his tastes for intellectual pursuits and scientific experiments bizarre if not unchristian, but Melbury wonders if he is just the sort of intelligent, cultured, gentleman Grace would be better suited to. But it is difficult to see through exteriors and into the heart of another’s character. Fitzpiers may be intelligent and high-born but his interests – intellectually, professional, romantically – are fickle, impulsive and non-committal.

Strict people of the highly respectable class, knowing a little about [Fitzpiers] by report, said that he seemed likely to err rather in the possession of too many ideas that too few; to be a dreamy ‘ist of some sort, or too deeply steeped in some false kind of ism. However this may be, it will be seen that he was undoubtedly a somewhat rare kind of gentleman and doctor to have descended, as from the clouds, upon Little Hintock.

Similarly, Grace may have benefited from her father’s investment in her education and undergone much change, but she remains a country girl at heart and can be happy with a simple life. And Grace is not the only one Fitzpiers has taken an interest in, nor is she the only one interested in either Winterborne or Fitzpiers.

He knew that a woman once given to a man for life took, as a rule, her lot as it came, and made the best of it, without external interference; but for the first time he asked himself why this so generally should be done. Besides, this case was not, he argued, like ordinary cases. Leaving out the question of Grace being anything but an ordinary woman, her peculiar situation, as it were in mid-air between two stories of society, together with the loneliness of Hintock, made a husband’s neglect a far more tragical matter to her that it would be to one who had a large circle of friends to fall back upon. Wisely or unwisely, and whatever other fathers did, he resolved to fight his daughter’s battle still.

The Woodlanders is the fourth Hardy novel I have read and I have enjoyed how the settings have kept changing through his fictional Wessex. From the busy, connected, rural setting of Far From the Madding Crowd; the isolated, backward setting of The Return of the Native; the country town of The Mayor of Casterbridge and now the secluded village surrounded by forest in The Woodlanders. In the characters of The Woodlanders, though, we can see shades of those we met in previous Hardy novels but perhaps with some added complexity.

Giles Winterborne, like Far From the Madding Crowd’s Gabriel Oak, is a hard-working, down-to-Earth man of simple tastes. Unlike Gabriel, he is more socially awkward and inept and, though both suffer misfortune that destroys their dreams of improved wealth, Giles’ misfortune is due to more than just bad luck as there was much he could have done in hindsight to prevent his fall.

Like Far From the Madding Crowd’s Bathsheba Everdeen, Grace Melbury has more education than she has opportunity to use it. Unlike Bathsheba, she has none of her ambition and drive. Or perhaps the difference is that Grace has not had the fortune of Bathsheba to engage it. Nor does she necessarily feel the confinement or claustrophobia of her place as The Return of the Native’s Eustacia Vye. Despite the options available to her, Grace is somewhat compliant to the wishes of her father.

Edred Fitzpiers’ behaviour may invite comparisons to Far From the Madding Crowd’s Troy, The Return of the Native’s Wildeve or The Mayor of Casterbridge’s Henchard. But Fitzpiers has more intelligence and, eventually, more conscience than Troy. He is also younger than Henchard and so, while his character may lead him towards making dangerous mistakes, he is still young enough to try to change and make amends.

What has not changed from earlier Hardy novels is the key theme of horrible fates for those who make a poor match in love, of a time when social classes are becoming blurred as people quickly rise or fall in fortune, and of women who bear the brunt of such dynamics.

The novel has some wonderful descriptive pieces of scenery and character which is not surprising given Hardy’s accomplishments as a poet.

And so the infatuated surgeon went along through the gorgeous autumn landscape of White-Hart Vale, surrounded by orchards, lustrous with the reds of apple-crops, berries and foliage, the whole intensified by the gilding of the declining sun. The earth this year had been prodigally bountiful, and now was the supreme moment of her bounty. In the poorest spots the hedges were bowed with haws and blackberries; acorns cracked underfoot, and the burst husks of chestnuts lay exposing their auburn contents as if arranged by anxious sellers in a fruit market. In all this proud show some kernels were unsound as her own situation, and she wondered if there were one world in the universe where the fruit had no worm, and marriage no sorrow.

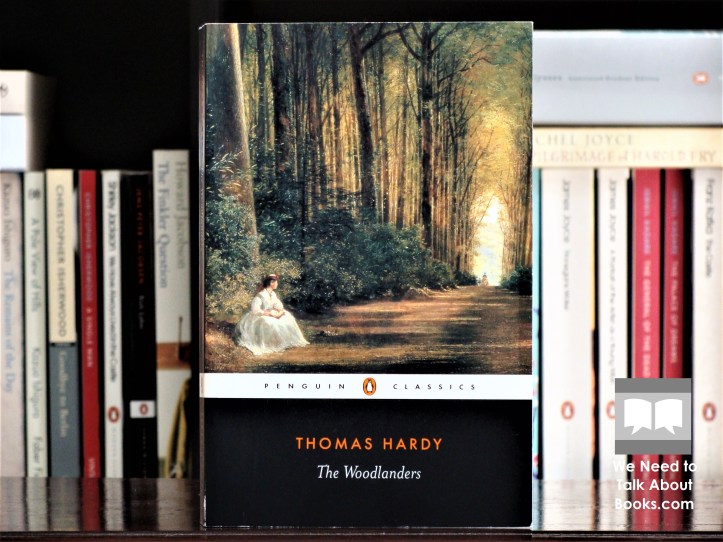

Despite this, the novel is very pacey. The chapters are short and the plot advances with each one. Other aspects of the novel, such as the frequent references to Norse mythology, the influence of new science – Darwinism and geology, the symbolism of the woodlands to the story, are a bit lost on me I’m afraid. Although Patricia Ingham, in her Introduction to this Penguin Classics edition, does make some interesting points, I am reluctant to overemphasise these factors.

Hardy is said to have thought of this novel of his as ‘quaint’. I am inclined to agree. Again, I find myself reluctant to be overly analytical here, or to be too critical or complimentary. It is neither a favourite nor forgettable but a pleasure to read. Yet ‘quaint’ is not quite the right word either. That might give the impression that this novel is inconsequential, a lightweight, when in fact it has quite a dark side, full of drama, heartbreak and of course, tragedy.

For reviews of other Thomas Hardy novels, see here.