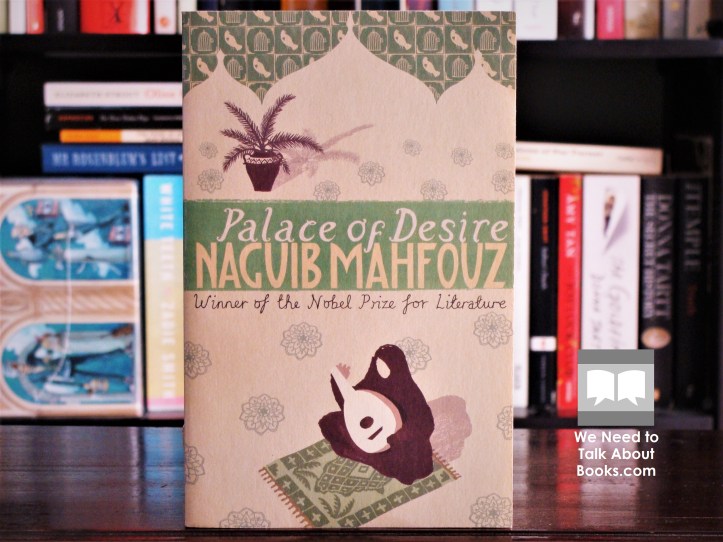

Palace of Desire is the second novel of Nobel Prize Winner Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo Trilogy. In it we follow 17-year-old Kamal as he deals with crises of faith and unrequited love in 1920’s Egypt.

Note – since this novel is the second part of a trilogy, this review contains spoilers with regards to the first novel; Palace Walk (see my review here).

Five years have passed since the death of Fahmy, the eldest son of Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad, shot during a demonstration against the British occupation of Egypt. In those five years Al-Sayyid Ahmad, out of repentance, has turned his back on his previous life of drinking, partying and adultery, neglecting his friends. He has even loosened the reigns on his previously tyrannical rule over his family. His wife, Amina is now permitted to leave the house to visit family and her beloved al-Husayn mosque. She can even state an opinion without having to fear his wrath. His two other sons, Yasin and Kamal, also enjoy greater freedom.

Al-Sayyid Ahmad, though, has started to return to his former vices. Resuming his nights out with his old friends, he has begun drinking again and is also tempted by the possibility of new affair. But there is a shock in store for Al-Sayyid Ahmad as the object of his desires, a young lute player named Zanuba, rejects his advances. Having never been rejected by a woman before, it is a humiliation he can barely tolerate, and his lust demands to be satisfied. Al-Sayyid Ahmad proceeds to ply the young woman with luxuries in the hope she may come around to indulging him in return. But more shock and humiliation is in store for Al-Sayyid Ahmad; he is unaware that the young woman was once the lover of his eldest son, Yasin.

Yasin is very much the same man from Palace Walk; a hedonist and a sexual predator. He still shares his father’s tastes for alcohol and adultery and still does not understand why his activities end in scandal and disaster while his father’s do not. Incapable of living the double-life his father does and having failed in his first marriage; Yasin is increasingly convinced the solution must be to marry a woman who would allow him to pursue his pleasures more-or-less openly. The choices he makes will risk estrangement from his stepmother and sets him on a collision course with his father.

You may presume from the title, as I did, that in Palace of Desire the focus of the trilogy shifts to following the life of Yasin. The title comes from the alley of Cairo (Qasr al-Shawq) where Yasin lives having inherited a house from his deceased mother. But in fact, the encroaching love triangle between Yasin, his father and Zanuba is the subplot of this novel; the main story – at least by volume – concerns Al-Sayyid Ahmad’s youngest son, Kamal.

When we left Kamal at the end of Palace Walk, he was a precocious 12-year-old boy, devoted to learning the Qur’an though with a childlike innocence that gets him into trouble when he questions the rules of religion and culture that contradict his sense for reason. In Palace of Desire we meet an internally tormented 17-year-old Kamal; a young man in a state of transition.

His troubles began when he realised the al-Husayn mosque, beloved by his family, does not in fact contain the remains of the Muslim saint; the tomb is merely symbolic. He increasingly realises that much of what he treasured in childhood is also an empty symbol. Intelligent, and with a deep devotion to religious studies as a child, his mother had hoped he would become an Islamic scholar like his grandfather. But attending an elite school has exposed him to new ideas and new friends that challenge the traditions he grew up with and the repression that keeps them in place. Western science and Darwin, as well as Muslim sceptics and reformers, have made him question his religion, culture and traditions.

He secretly promised his mother he would consecrate his life to spreading God’s light. Were not light and truth identical? Certainly! By freeing himself from religion he would be nearer to God than he was when he believed. For what was true religion except science? It was the key to the secrets of existence and to everything really exalted. If the prophets were sent back today, they would surely choose science as their divine message. Thus Kamal would awake from the dream of legends to confront the naked truth, leaving behind him this storm in which ignorance had fought to the death. It would be a dividing point between his past, dominated by legend and his future, dedicated to light. In this manner the paths leading to God would open before him – paths of learning, benevolence and beauty. He would say goodbye to the past with its deceitful dreams, false hopes and profound pains.

Each week, he goes to a wealthy part of Cairo where his best friend, Husayn Shaddad, lives in his parent’s mansion. There Kamal and his school mates discuss politics, religion and what they are going to do with their lives now that their schooling is reaching an end. Wealth is not the only thing that separates Kamal from his friends. He still wears his fez, performs some religious duties and is passionately loyal to the political forces his martyred brother supported. His friends poke gentle fun, pointing out that Kamal is much more conservative, traditional and religious than he sometimes thinks he is. Amongst the Europeanised Shaddad family, who lived in exile in Paris for a time, he witnesses husband and wife walking arm-in-arm, the wife treated as an equal by her husband and is shocked to see Muslim dietary restrictions openly flouted.

But Kamal’s greatest source of torment are his feelings for his best friend’s sister, Aïda. Though he knows his feelings are unlikely to be requited as she is older and from a wealthy family, he can’t help but indulge the fantasy that he may one day be united with the girl he can only think of in terms of unrealistic, angelic perfection. Sensitive and self-conscious about his large head and big nose, Kamal feels like Quasimodo and is tortured by his unrequited love for Aïda.

“But how can angels love you?” he wondered. “Call up her blissful image and contemplate it a little. Can you imagine her unable to sleep or left prostrate by love and passion? That’s too remote even for a fantasy. She’s above love, for love is a defect remedied only by the loved one. Be patient and don’t torment your heart. It’s enough that you’re in love. It’s enough that you see her. Her image shines into your spirit and her dulcet tones send intoxicating delight through you. From the beloved emanates a light in which all things appear to be created afresh. After a long silence, the jasmine and the hyacinth beans begin to confide in each other. The minarets and domes fly up over the evening glow into the sky. The landmarks of the ancient district hand down the wisdom of past generations. The existential orchestra echoes the chirps of the crickets. The dens of wild beasts overflow with tenderness. Grace adorns the alleys and side streets. Sparrows of rapture chatter over the tombs. Inanimate objects are caught up in silent meditation. The rainbow appears in the woven mat over which your feet step. Such is the world of my beloved.”

Unlike Palace Walk, in Palace of Desire, the influence of French and existential writers Mahfouz is said to have been influenced by, is plain to see. Much of the novel is of Kamal’s internal ponderings as he questions the meaning of love, the purpose of life, the point of traditions and the existence of God. It is wonderfully evocative and there are many beautifully written passages. Where Western readers may find Palace Walk difficult to relate to, the same cannot be said for Palace of Desire with its focus on a young adult trying to figure out life.

Love seemed to be suspended over his head like destiny, and he was fastened to it with bonds of excruciating pain. It resembled a force of nature more than anything else in its inevitability and strength. He studied it sadly and respectfully.

The problem’s not that the truth is harsh but that liberation from ignorance is as painful as being born. Run after truth until you’re breathless. Accept the pain involved in recreating yourself afresh. These ideas will take a life to comprehend, a hard one interspersed with drunken moments.

Set roughly between 1924 and 1927, Palace of Desire is also a less political novel than Palace Walk. Although, Kamal and his friends do have some lively political debates and Kamal even comes to see his relationship with Aïda as analogous to that of Egypt and the patriots who fight for her. The background of a country on the verge of democracy and modernity struggling to let go of its long-held traditions and devoted religious following; where alcohol consumption, drug use and sexual affairs occur but in secret; is clear throughout and mirrored in the story of transition within the very traditional al-Jawad family.

The one criticism I do have of Palace of Desire is the way it ended. With trilogies, you expect the first book to be an almost stand-alone story; as if even the author is unsure whether there will be cause to continue. The second book often necessarily ends openly with unanswered questions so as to bridge to the third book. As I neared the end of Palace of Desire I thought it was breaking with this expectation and was presenting a fairly complete story with little room for continuance. Until the final chapter that is, where events leave the reader without closure. I felt Mahfouz left this a little late. The fact that the events of the final chapter occur some eight months after the previous chapter also make this ending a little forced.

But this is a minor quibble of an otherwise excellent novel. More satisfying, it provides plentiful reward for those who persisted with the first novel.

For my reviews of the other novels in the Cairo Trilogy, see here.

[…] ← Book Review: God’s War Book Review: Palace of Desire → […]

LikeLike

Due to the large influence of the Lord of the Rings movies, I always think books that must continue, like those in a trilogy, should end when characters get to the edge of one type of terrain and are about to walk on another. 🙂

LikeLike

True. I think the original Star Wars trilogy have also planted the idea that the second story in particular should be open-ended. Thanks for your comment!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] ← Book Review: Palace of Desire […]

LikeLike

[…] Note – since this novel is the third part of a trilogy, this review contains spoilers with regards to the first two novels; Palace Walk and Palace of Desire. […]

LikeLike

[…] me review of the second book in the Cairo Trilogy, Palace of Desire, and the third, Sugar […]

LikeLike