Frankenstein is a novel that has never left the popular imagination since it was first published in 1818 and it probably never will. A dark gothic fantasy, an early science fiction, or a ‘precursor to the existential thriller’; its arresting power has captured every generation. Possibly it strikes at something disturbing in human nature.

Robert Walton can barely contain his excitement. He spent his childhood dreaming of adventure. As he grew up it seemed a remote possibility. A career as a poet floundered. But an inheritance from a cousin has made his dream a reality.

There is something at work in my soul, which I do not understand. I am practically industrious – painstaking; a workman to execute with perseverance and labour: – but besides this, there is a love for the marvellous, a belief in the marvellous, intertwined in all my projects, which hurries me out of the common pathways of men, even to the wild sea and unvisited regions I am about to explore.

Walton’s chosen target is the frozen north. He has managed to procure a ship and a crew. The only thing he wishes for is a companion who shares his thirst for adventure. The north is a region that promises to combine the extremes of danger and mystery. The source of magnetism, unknown astronomy, unexplored sea routes and unexplained lights is matched by the perils of freezing temperatures, ship-wrecking ice and utter isolation from any supply or chance of rescue. Writing to his sister, Margaret, from St Petersburg, Walton can hardly wait.

He is not long disappointed. Early in their adventure, their ship is boxed in by ice and they dare not risk proceeding further. And they may not be alone. Through the distant mist they think they can make out the eerie shape of a huge figure making his way on the ice on a sled pulled by a team of snow dogs. The next day they spy another man with a dog sled. This man, though, is clearly in need of rescue and the crew pick him up from the ice barely alive.

It takes several days to revive the man. Walton is pleased that he might have found a companion, but when Walton tells him the reason for his journey, Victor Frankenstein breaks down in tears at the thought that Walton is suffering from the same obsession that has ruined his life. Victor has a warning for Walton of the awful consequences of Walton’s ambition. This warning is Victor’s life story.

New readers to Frankenstein might be surprised by how many of their ideas of the story do not originate in the novel but from how the basic concept has been borrowed and reimagined in various other formats. Victor Frankenstein is not the ‘mad scientist’ of the images those words might conjure up. The use of electricity, the foraging from cemeteries, is hinted at but not given the weight of other tellings. And Victor’s creation is certainly not the zombie-like, brain-dead, monster but an articulate, thinking, feeling being that is human in all but appearance.

The novel’s first clever trick is its structure. If the story began with Victor Frankenstein telling you his life story, I suspect many readers would not venture far. By instead beginning with Robert Walton’s letters to his sister, the reader is instead dropped into the icy waters of the Arctic and made to tread water. Robert’s infectious description of his thirst for adventure, despite the dangers; his romantic desire for knowledge having been seduced by the mysteries of the far north where none have ventured before, effectively harpoon the reader. It also foreshadows and creates sympathy for Victor’s similar motivations to pursue his own tragic quest.

Another aspect that made Frankenstein a landmark was that its themes were far more sophisticated than the gothic novels that preceded it. While sharing elements with other classic plots types, Frankenstein did offer something new to readers. Most obvious is the nature of the monster itself. Traditional stories would have the reader siding with the ‘hero’ in their quest to defeat the monster. Frankenstein turns this around and forces us to ask who is the real ‘monster’ and who, if anyone, is the ‘hero’.

Victor struggles to articulate why he despises his creation other than to say he finds its appearance hideous. Although it is likely that the real reason Victor finds his creation so abhorrent is that it is a reminder of his obsession and folly; his turning away from the light. The prejudice towards the creature’s appearance is confirmed by the creature’s own experiences where he finds if it was not for his appearance he would be acceptable to society. The blatant prejudice towards the creature who then uses this to justify his turn to violence leaves the reader to wonder if there are any heroes at all in this novel or only monsters.

I think the part of the novel modern readers struggle with is Part 2. This is the part mostly narrated by the creature. He tells Victor who tells Robert, who tells his sister (and us) what became of him after Victor fled his laboratory and abandoned him. The creature relates how he learned to understand, speak and read language, how he learned to provide for himself, his encounters with fire and people and, most of all, about how he learned about his nature and how others perceive him. The characters in this Part allow us to compare and contrast the creature’s experience of rejection with others who are also exiled from society.

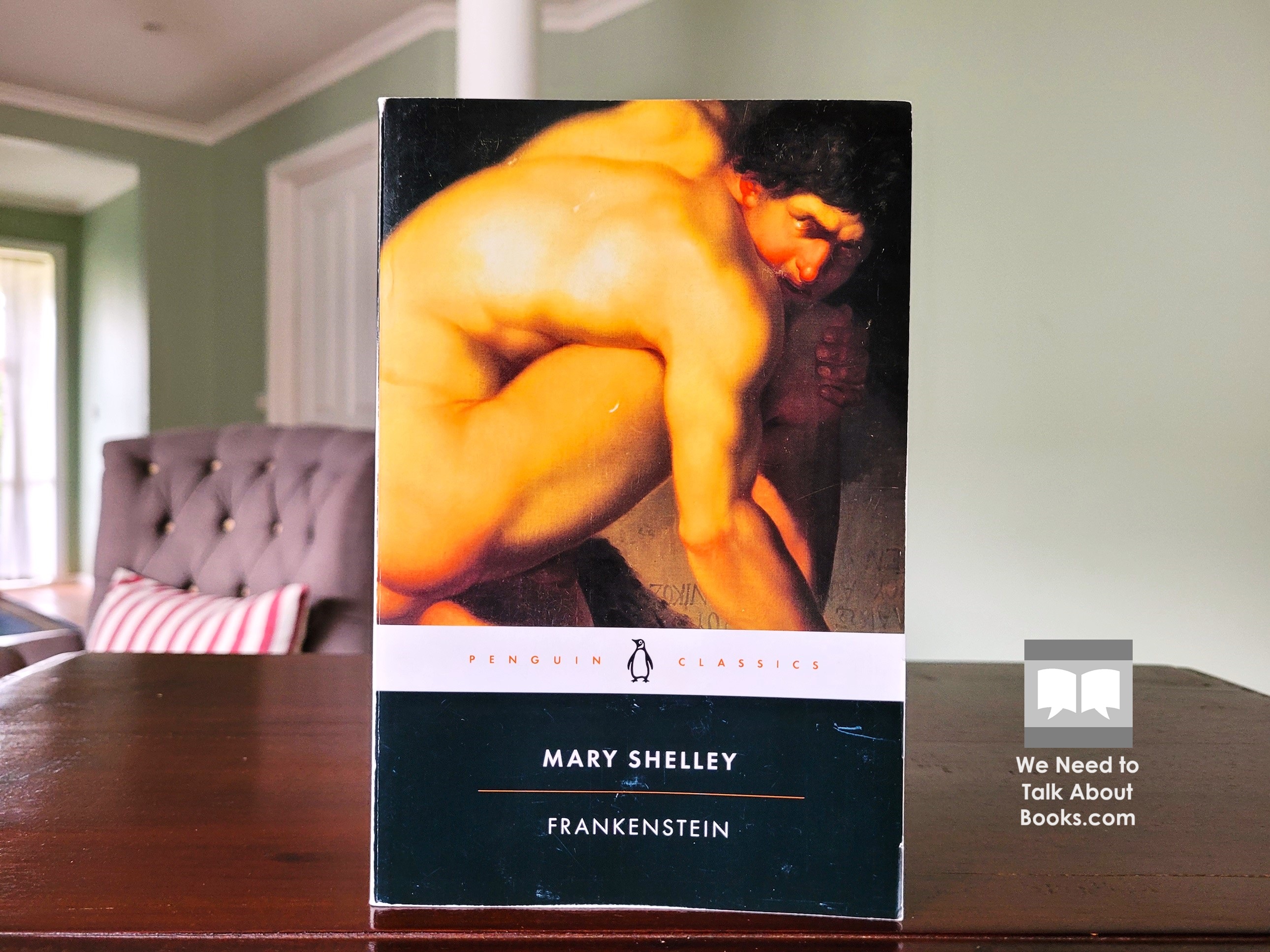

Modern readers may find this Part a bit strange, a bit unconvincing or a bit dull compared to the rest of the novel. Maurice Hindle in the Introduction to this Penguin Classics edition offers an explanation for what this Part is about.

Besides its role in the development of the plot, Hindle suggests this Part exemplifies Mary Shelley’s beliefs concerning theories of mind. In particular, the theories of the British philosopher John Locke (1632-1704). In Locke’s view, the mind is a ‘blank slate’ or tabula rasa at birth. The development of the mind is therefore formed in response to experience. It is an argument supporting a strong role for nurture over nature for the development of the mind. As well as this philosophical take, the themes of isolation and alienation were prevalent in the Romantic era and are at work in this Part of the novel.

Putting aside the question of whether the modern science supports the argument (see Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate if you are interested), Mary Shelly is showing us here that, while the creature’s physical attributes have been designed by Victor, his non-physical attributes are a product of his experiences. From his acquiring of language to his moral outlook, these are the result of how he feels the world has treated him and what place, if any, the world has for him. If the creature is lacking in these regards, it may not be inherent in his nature as Victor seems to believe, but it is society, including Victor, that has responsibility. Again, we are found asking who is the real monster?

The origin story of Frankenstein is one that has become one of the most famous in literary mythology. This is the tale where, during a visit to see Lord Byron in Geneva, stuck indoors due to bad weather, those present occupied themselves by reading German ghost stories before Byron proposed a ghost story competition between them. And from this experience the then eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley created the germ of what became Frankenstein. There is of course more to the story than the famous anecdote.

Unlike many novels, with Frankenstein there is no mystery as to Mary Shelley’s influences and inspirations. This is because so much of her life is laid bare for us to see. Apart from being famous for her own achievements, she is also the child of a famous mother and father. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), was a philosopher, feminist and author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women. Wollstonecraft died shortly after giving birth to Mary Shelley due to complications with the birth. Mary Shelley’s father was the political philosopher William Godwin (1756-1836) and her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), was a writer who came to be regarded as one of the major English Romantic poets.

We therefore have a great deal of information about Mary Shelley’s life. We know where she lived and travelled and with whom, what she was reading and writing and who were her visitors at home and others in her orbit. Hindle argues that features of Mary Shelley’s biographical, philosophical and literary life feature in the novel.

For example, Mary was present when Samuel Taylor Coleridge visited and read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which influenced Frankenstein. Another visitor to the Godwin house was Humphrey Davy, a pioneer of electrochemistry and an advocate for the unlimited powers of science, much admired by Percy Shelley. Byron and Percy Shelley had been discussing the possibilities of animating life, the experiments of Erasmus Darwin and galvanism during the time in Geneva when Mary Shelley was coming up with her ghost story.

We also know a lot about what Mary Shelley was reading. She was a fan of Samuel Richardson, Madame de Genlis and read a lot of gothic novels, whose influences can be seen in Frankenstein. More philosophically, she also heavily read Milton, Rousseau and the aforementioned Locke. Again, the influence of their political, religious and existential ideas are evident in the novel. Milton and Paradise Lost was revered in the Godwin house and Hindle suggests the creature in Frankenstein turns from being like Milton’s Adam to Milton’s Satan.

But Paradise Lost excited different and far deeper emotions. I read it, as I had read the other volumes which had fallen into my hands, as a true history. It moved every feeling of wonder and awe, that the picture of an omnipotent God warring with his creatures was capable of exciting. I often referred the several situations, as their similarity struck me, to my own. Like Adam, I was apparently united by no link to any other being in existence; but his state was far different from mine in every other respect. He had come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care of his creator; he was allowed to converse with and acquire knowledge from beings of a superior nature: but I was wretched, helpless, and alone. Many times I considered Satan as the fitter emblem of my condition; For often, like him, when I viewed the bliss of my protectors, the better goal of envy rose within me.

Percy Shelley’s influence in the novel also can’t escape mention. It has been suggested that Victor Frankenstein is at least partly based on Mary Shelley’s husband. They share an interest in science that runs to an obsession and a faith in Man’s unlimited creative powers. The theory that Percy is the real author of Frankenstein (the novel was originally published anonymously) has never faded no matter how unreasonable the claim seems. If anything, Frankenstein is more reliably interpreted as a critique of Percy’s beliefs and character, showing the dark side of where it might eventually lead. To me, it would require a level of self-awareness that does not credit him as the author of the novel.

I did once hear that Mary Shelley denied that Frankenstein was about Man’s relationship with God but that may not be true and I cannot find a source for that now. In any case, it is an interpretation that is difficult to completely reject given that the story concerns a battle between Creator and Creation with many references to Adam. Victor rejects his creation and this rejection is keenly felt by the creature who asks like a child to a distant father (something Mary Shelley also experienced) shouldn’t the Creator have some responsibility for the happiness and wellbeing of his creation?

I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural Lord and king, if thou wilt also performed thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample upon me alone, to who thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember, that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen Angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.

The other common interpretation of Frankenstein is that it is a warning against the pursuit of scientific knowledge and the powers it unleashes. The subtitle of the novel is ‘The Modern Prometheus’. In classical mythology, Prometheus steals fire from the gods and gifts it to mankind. Like a literal divine spark his act sets humans on a path towards technology and civilisation. Prometheus is punished by the gods for his act and is therefore a saviour and martyr for mankind.

Prometheus Bound by the ancient Greek tragedian Aechylus is the most famous version of the myth. Both Byron and Percy Shelley were admirers of it and wrote their own Prometheus works. But as Hindle points out, the Greek and Roman versions of the Prometheus story differ. A comparison between the two again makes one wonder if he is a ‘hero’. Hindle suggests Mary Shelley combines the two in Frankenstein.

‘The ancient teachers of the science,’ said he, ‘promised impossibilities, and performed nothing. The modern masters promised very little; they know that metals cannot be transmuted, that the elixir of life is a chimaera. But these philosophers, whose hands seem only made to dabble in dirt, and their eyes to pour over the microscope or crucible, have indeed performed miracles. They penetrate into the recesses of nature, and show how she works in her hiding-places. They ascend into the heavens: they have discovered how the blood circulates, and the nature of the air we breathe. They have acquired new and almost unlimited powers; they can command the thunders of heaven, mimic the earthquake, and even mock the invisible world with its own shadows.’

Such were the professor’s words – rather let me say such the words of the fate – enounced to destroy me. As he went on I felt as if my soul were grappling with a palpable enemy; one by one the various keys were touched which formed the mechanism of my being: chord after chord was sounded, and soon my mind was filled with one thought, one conception, one purpose. So much has been done, exclaimed the soul of Frankenstein, – more, far more, will I achieve: treading in the steps already marked, I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation.

Modern audiences are familiar with the theme that danger lies in the pursuit of knowledge. If fictional takes are insufficient we have plenty of examples from history that can be interpreted that way. However, it can be reasonably argued that this is not Mary Shelley’s message in Frankenstein. Rather, the tragedy is the consequence of narrowmindedness. It is not Victor’s ambition that is his undoing, even if he sometimes seems to think so himself. Rather, it is that in his obsession he lost perspective, balance and his moral centre.

A human being in perfection ought always to preserve a calm and peaceful mind, and never to allow passion or a transitory desire to disturb his tranquilly. I do not think that the pursuit of knowledge is an exception to this rule. If the study to which you apply yourself has a tendency to weaken your affections, and to destroy your taste for those simple pleasures in which no alloy can possibly mix, then that study is certainly unlawful, that is to say, not befitting the human mind. If this rule were always observed; if no man allowed any pursuit whatsoever to interfere with the tranquillity of his domestic affections, Greece had not been enslaved; Caesar would have spared his country; America would have been discovered more gradually; and the empires of Mexico and Peru had not been destroyed.

Victor’s attempt to be a creator of new life is in a sense blasphemous but Mary Shelley is not making an argument in favour of a return to traditional Christianity either. It seems more inclined to find a new moral perspective. One for which there is an urgent need in the face of the new powers technology is creating.

The Enlightenment period in which Frankenstein was written was one of great transition – ‘between doubt and Darwin’. In 1828, ten years after Frankenstein was first published, Friedrich Wöhler reported his synthesis of urea – a substance produced by living organisms – using entirely inorganic ingredients without any need to involve a “vital force”. In 1840 Justus von Liebig published his text on organic chemistry arguing that plants absorb carbon from the atmosphere and nutrients from non-organic materials in the soil, further destroying the idea of the vital force. These results were very controversial at the time. It had been assumed there was a strong separation between the materials of the living and the non-living world.

Frankenstein captures the excitement and fears of an era where previous certainties had crumbled to dust leaving the unsettling feeling of being untethered to any physical, mental, spiritual or moral reality.

I first read Frankenstein probably almost twenty years ago and declared it one of my favourite books. In recent years I have decided to reread these favourites and some others that I believe deserve another look. The results have been up and down. Rereading All Quiet on the Western Front saw me demote it from my favourites list. On the other hand, rereading Catch-22 affirmed its place on my favourites list and as probably my favourite novel overall.

Reading Frankenstein a second time, I am not sure how to place it. I probably did not enjoy it as much as I did the first time. That Part 2 is a bit puzzling and difficult. But what Frankenstein does well it does exceptionally well. I am thinking here of the intrigue and anticipation it builds in the Part 1 and a few specific scenes that stick in the memory. The turns in plot that I had not remembered from my first experience still had the power to surprise me. One in particular turns the plot in unexpected ways.

Reading it again, I also love Mary Shelley’s descriptive writing. She gives a real sense of time and place to the reader that is evocative and makes for some of the powerful scenes I mentioned. Despite the fact that the use of the pathetic fallacy was a familiar trope in gothic novels, some contemporary novels I have read recently have been disappointingly deficient in this regard. Mary Shelley really puts them to shame.

Frankenstein has lost none of its power to captivate and horrify. I also doubt whether we will ever lose our ability to reanimate it to suit our circumstances. In our post-Enlightenment world it continues to agitate us and remind us of our worst fears.