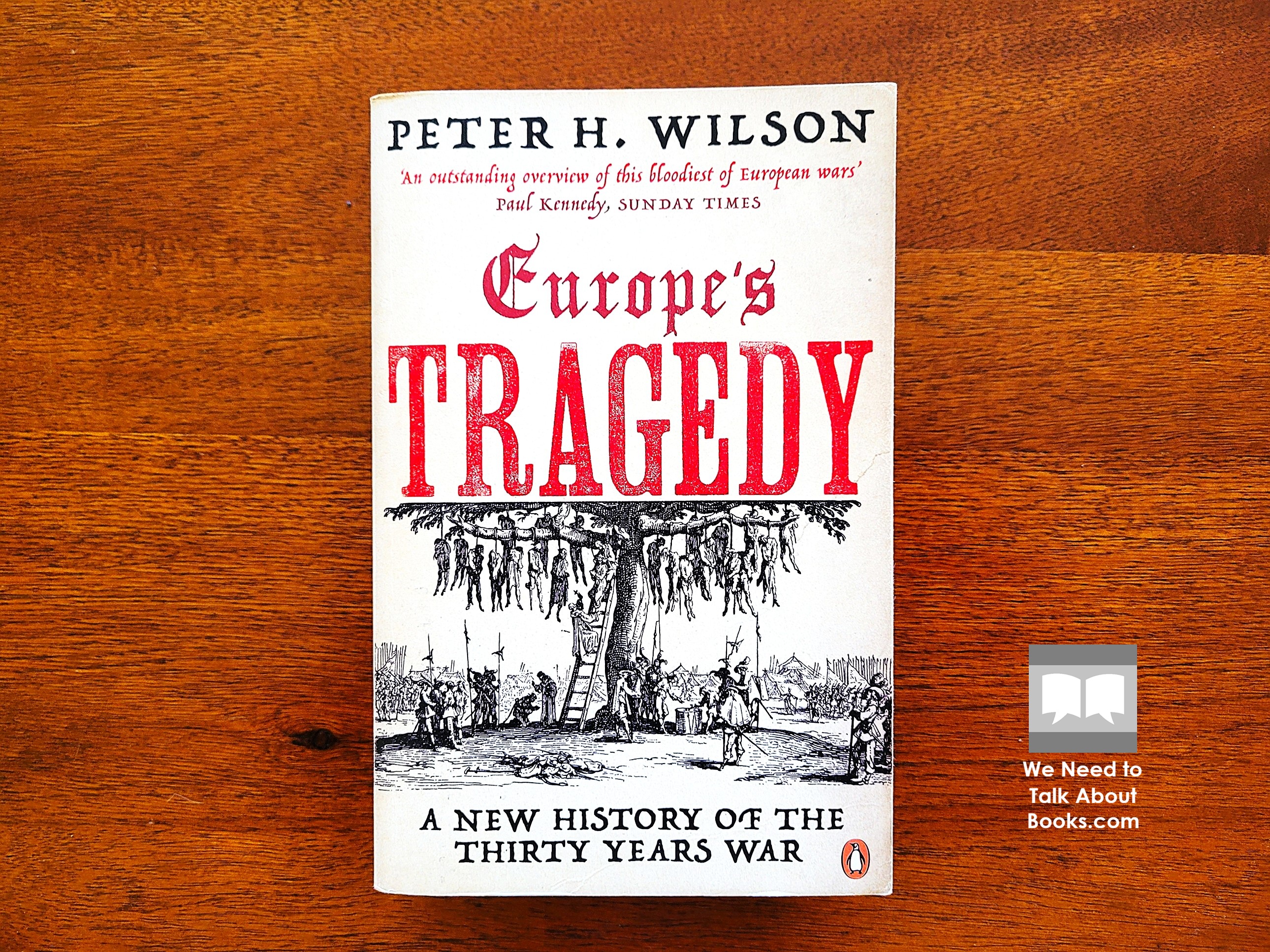

Some subjects are so vast and intricate that any attempt to contain them within a single volume seems doomed to disappoint. Yet, from time to time, a historian manages not merely to compress but to command such material, producing a work that feels definitive rather than reductive. I am sceptical of sweeping narratives – especially of conflicts as tangled and consequential as the Thirty Years War – but there are books that earn the distinction of being the one you would press into a reader’s hands if they were to read only a single account. With Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War, Peter H. Wilson has achieved precisely that: a study of intimidating breadth and depth that meets the complexity head-on and, remarkably, succeeds.

Some topics for nonfiction are too large and complex to be treated comprehensively in a single volume. Though that does not stop many from trying. In fact, I can probably count more that I think are successes than failures. That may be owing to a biased sample on my part – I would be very sceptical of a book that purports to tell the entire history of the Second World War for example.

But there are books that can meet the standard of ‘if you were only ever going to read one book on this subject, this should be it’. Simon Schama’s Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution is often mentioned as one. Though I did not agree and was left feeling incomplete when I read it. Adrian Goldsworthy’s Caesar: The Life of a Colossus is one that I think meets the standard. Christopher Tyerman’s God’s War: A New History of the Crusades is another.

Diarmaid MacCulloch’s The Reformation would also be a contender and, as unlikely as it sounds, his A History of Christianity is another. I see that my wife has copies of John Keegan’s The Second World War and JM Roberts’ A History of the World. Perhaps there is value in books that take a wider view and a larger context and can overcome my scepticism that they can do their subjects justice with their findings. (I have just started reading Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy and he gives a brief comment on the pros and cons of taking a wide view)

Having now read Peter H Wilson’s Europe’s Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War I have another example of a book that I feel meets the standard.

Had I known of the long-lasting impact of this conflict I might have read this book before Peter Watson’s The German Genius: Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution and the Twentieth Century. Also an excellent book, it begins with the devastation of the Thirty Years War and path of Germany and its people to resurrect itself.

Europe’s Tragedy starts out the way anyone hoping such a book would. That is, Wilson delves into the difficulties in tackling the subject and the weaknesses of previous attempts to do so. The Thirty Years War is an extremely complex subject and previous attempts have overemphasised some factors at the expense of others. Each nation involved had their own interpretations of the War and those interpretations have also changed over time yet have always seemed to conform with the priorities of the period they were written in.

To cover all aspects would require knowledge of at least fourteen European languages, while there are sufficient archival records to occupy many lifetimes of research. Even the printed material runs to millions of pages; there are over four thousand titles just on the Peace of Westphalia that concluded the conflict. The sheer volume of evidence has affected how previous histories have been written. Some cut through the detail by fitting the war into broader explanations of Europe’s transition to modernity. Others give more scope to personalities and events but often signs of fatigue set in as the author approaches the mid-1630’s. By then the heroes and villains giving life to the opening phases were largely dead, replaced by other figures ignored by posterity. There is a rush to wrap up the story and the last thirteen years are compressed into a quarter or less of the text, much of which is devoted to discussing the peace and the aftermath.

In contrast, Wilson promises to correct the errors of the past, provide a more even coverage and view the War on its own terms instead of within general European history. Wilson cites three major ways his take will provide a distinction from past ones.

One I will share is on the matter of religion. Previous interpretations never questioned that the War was a war of religion between Catholic and Protestant forces. Wilson points out that the logic used to reach that conclusion could also be used to argue that the War was about the impact of modernisation and secularisation. Wilson does view the War as a religious war only to the extent that everyone at that time was religious and that religion guided much of their public and private action. The distinction that must be made, argues Wilson, is not between the relative zeal of moderates and fundamentalists but in the link between faith and action. The moderates were not necessarily more modern, rational or secular but were more pragmatic and did not see religious goals in the war.

As a reader, it was difficult to disagree. Following the conflict through the years and seeing captured soldiers routinely fighting for the other side for pragmatic reasons; generals joining or exiting the war for decidedly non-religious reasons; monarchs and other leaders seeking a secular peace in word and deed, and some even pledging to convert. To view the War as one of religion seems an obvious oversimplification.

That being said, Wilson emphasises the importance of understanding the religious issues of the time for understanding the war. To understand that religion played a role in the outbreak of the war, how faith related to disputes of earthly power and the differences between religious identities – Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, etc – after the Reformation.

Also essential to understanding the War is understanding the Holy Roman Empire. The Empire covered all of what is now Germany, Austria, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, much of Western Poland, Alsace, Lorraine, most of the Netherlands and Belgium and Northern Italy. Wilson describes its cities and communities; its noble families and three groups of Lords; its constitution, political culture and what it symbolised – a late-medieval idea of a single Christendom and a continuation of the Roman Empire.

I was only up to page thirty-six of the Introduction and was already feeling thoroughly overwhelmed by the complexity – but in a good way.

Europe’s Tragedy is divided into three parts. The first deals with the origins of the War, the second with the War itself and the third with the War’s impact and long-term significance.

As well as covering the religion and Holy Roman Empire, Part One has to provide detail of social, political and religious events in Austria; war with Turkey and its consequences; Spain and the Spanish Hapsburgs; the Dutch Revolt; the French Wars of Religion; and similar discussion of Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Switzerland, Belgium and much more.

After almost 270 pages we are ready for the war to begin.

Understandably, for such a large, complex and evolving conflict, covering the war period itself is a large portion of the book. For those who like their war history books, Wilson will not disappoint. Since we are dealing with battles in the early seventeenth century, the level of available detail may not match modern conflict. But in Europe’s Tragedy, Wilson provides maps and details of how each major battle played out and readers will find themselves well engaged with the action.

Between the battles, Wilson provides a lot of context. Political and economic developments and their impact on the War’s progress keep the reader appreciating the factors that can turn tactical victories in battle into strategic defeat in the War. Mini-biographies of the major leaders and commanders were often fascinating and were one of the main appeals of the book for me.

At [the head of the Palatine Cause] was Count Ernst von Mansfeld, one of the war’s most controversial figures. His motives remain unclear and his actions duplicitous. To most, he appears the archetypal mercenary who has come to characterise soldiers generally for this period. Whereas the controversy surrounding Wallenstein centres on his political ambitions, only baser motives are attributed to Mansfeld. Perhaps the key to understanding this complex man is his illegitimate birth as the thirteenth, natural son of Peter Ernst, count of a small territory in Upper Saxony and a Spanish field marshall. With no prospect of inheriting the county that, in any case, his father had to share with numerous relations, Mansfeld chose a military career, hoping to secure both legitimacy and reward. His lack of status made him quick to take offence and won him little sympathy. Along with plain bad luck, this frustrated hopes of rapid advancement and left him with a sense of grievance against the Habsburgs, heightened both by their failure to reimburse his expenses and because they twice removed him from command for his own mistakes. Rudolph II eventually declared him legitimate after the Turkish war, but he sought recognition from others, for example being ennobled by the Duke of Savoy in 1613. He defected to the union during the first Jülich crisis in 1610, but only after he had been captured. Though he tolerated Protestantism, he had been raised a Catholic and there is no clear evidence he converted. Certainly, he was disliked by those with genuine faith and it seems his allegiance to his new employers was determined by better prospects and lingering animosity towards the Habsburgs.

As well as the mini-biographies, there were several other types of diversion in this part of the book. One that I would like to share were on the rapid development in warship design during this period. Described in the context of the parallel war between the Spanish and the Dutch.

The Dutch were gradually increasing the size of their ships, from 80 to 160 tonnes by 1590 to 300 or 400 tonnes thirty years later, but by then the Dutch East India company (VOC) already had 1,000-tonne ships for its long voyages of armed trade. Large warships could carry up to 100 guns and were prestige objects. Gustavas Adolphus ordered his Dutch naval architect to oversee the construction of four great ships in Stockholm. The principle one, dignified by the name Vasa, displaced 1,400 tonnes, and carried 64 bronze guns and 430 sailors and marines. The desire to load it with ordnance meant the gun ports were too close to the water line and it capsized and sank in a light breeze on its maiden voyage in August 1628. The episode illustrates the risks and costs of experimenting with new technology and assembling naval power.

Another was a section on war financing. Wilson provides a great explanation allowing the reader to appreciate the complexity of practices of the time. It serves to put the reader in the period and provide a distinction to modern practices and absolves us of our assumptions and preconceptions.

Also, like the best of historians, while Wilson keeps reminding us of the larger forces at work he dissuades us from accepting any part of the history as inevitable. Several battles could have ended differently. Many well-intentioned attempts at peace produced the opposite result. Many others were rejected even though they closely resembled the final settlements. And even when the War ended there were several instances where it could have easily resumed if it were not for everyone’s exhaustion.

But it is a very long and complex book about a long and complex period of history. I did find the going rough at times. As the years go by, appreciating the impact of new developments and remembering the large number of key personnel by name was very challenging. Keeping interested though was not difficult.

In the last section of the book, Wilson discusses the aftermath of the war and what we might conclude from it. Again, for readers who lead with scepticism and wish to be persuaded by reason and evidence, Wilson speaks a language we can trust. For everything we might conclude from this history, he provides plenty of counterargument and conflicting information.

Interpretations of the peace settlement have broadly assumed one of two positions. Political scientists are generally positive, seeing the treaties as the birth of the modern international order based on sovereign states. Historians have, until recently, been largely negative, claiming ‘the war solved no problem. Its effects, both immediate and indirect, were either negative or disastrous. Morally subversive, economically disruptive, socially degrading, confused in its causes, devious in its course, futile in its result, it is the outstanding example in European history of meaningless conflict.’

Wilson begins by arguing against previous suggestions that the Thirty Years War was a general European war or that it was even the real First World War. Through the rest of the section Wilson takes the reader bit by bit through what the War was and what it was not. He covers the peace settlement and what we can interpret from it; the impact of the war demographically, economically and culturally; and what we can say of the people’s experience of the war and how it changed them.

Again, to take one example of the role of religion in the peace, Wilson argues that the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years War represents the birth of a modern international order, where sovereign states are treated as equals in negotiation within a common secularised legal framework.

Despite these shortcomings, the [Westphalian] Congress was a ground-breaking event. medieval church councils with the closest precedent, but this was the first truly secular international gathering. It drew on established protocol and negotiating styles, but its sheer scale and the complexity of the issues compelled innovation and dissemination of common guidelines. First and foremost, the Congress eroded the medieval principle of hierarchy. The presence of so many representatives from rulers of different rank required a new, simpler form of interaction. It was agreed that all Kings had the title of ‘Majesty’ and that all royal and electoral ambassadors were to be addressed as ‘Excellency’ and could arrive in a coach pulled by six horses. Such matters were far from trivial. They represented a major step towards the modern concept of an order based on sovereign states interacting as equals, regardless of their internal form of government, resources, or military potential. The Congress established a new way to resolve international problems through negotiation among all interested parties. Attempts to resolve later European wars drew directly on this precedent, notably the Congress of Utrecht (1711-13) and Vienna (1814-15), and the method was extended in line with the changing global order at the Paris Conference of 1919 and, ultimately, with the United nations.

Bickering over religious issues continued and religion clearly mattered but theologians no longer had influence over policy. Though Treaties did not diminish the power of the Emperor and required him to compromise with estates and princes to a greater degree, the role of religion in internal politics was greatly diminished. Politics could not be completely secularised but the Thirty Years War discredited the idea of using force to make confessional gains.

All that being said, Wilson says the Peace was very much a Christian Peace. He says it is a misconception that the Peace took religion out of politics or was fully secular. Instead, the Treaties were full of new religious laws. The Empire remained Christian, toleration was extended to more Christian denominations but noticeably excluded Jews and Muslims. This was certainly not secularism or toleration in a modern sense.

More than a hundred and fifty years after the end of the Thirty Years War it continued to have cultural impact as Romantic writers of Central Europe took up the story. To them, the narrative to use was of the innocent victim, of a war that destroyed absolutely everything and of a triumphant return from the ashes.

The war occupies a place in German and Czech history similar to that of the civil wars in Britain, Spain and the United States of America, or the revolutions in France and Russia: a defining moment of national trauma that shaped how a country regards itself and its place in the world. The difficulty for later generations in coming to terms with the scale of the devastation has been compared to the problem of historicising the Holocaust. For most Germans, the war came to symbolise national humiliation, retarding political, economic and social development and condemning their country to two centuries of internal division and international impotence.

[…]

Public opinion surveys carried out in the 1960s revealed that Germans placed the Thirty Years War as their country’s greatest disaster ahead of both world wars, the Holocaust and the Black Death.

It is a narrative that historians from the early Twentieth Century onward have poured cold water over. But it is not so easy to dispel a story that has become a part of a cultural identity with facts and evidence. The impact of this long, complicated war from four centuries ago continued to have resonance with people and in turn influenced events much closer to our time. It may not have been the real First World War but its interpretation may have been a part of the story of the ones that followed and leaves it an important chapter of history to learn something about.