I avoided Holy Cow! by Sarah Macdonald for years and only came to it by a chance encounter and with a lot of scepticism. But the complexities of India allow for a multitude of perspectives on an uncountable number of possible experiences. Sarah’s take is a valuable one worth hearing.

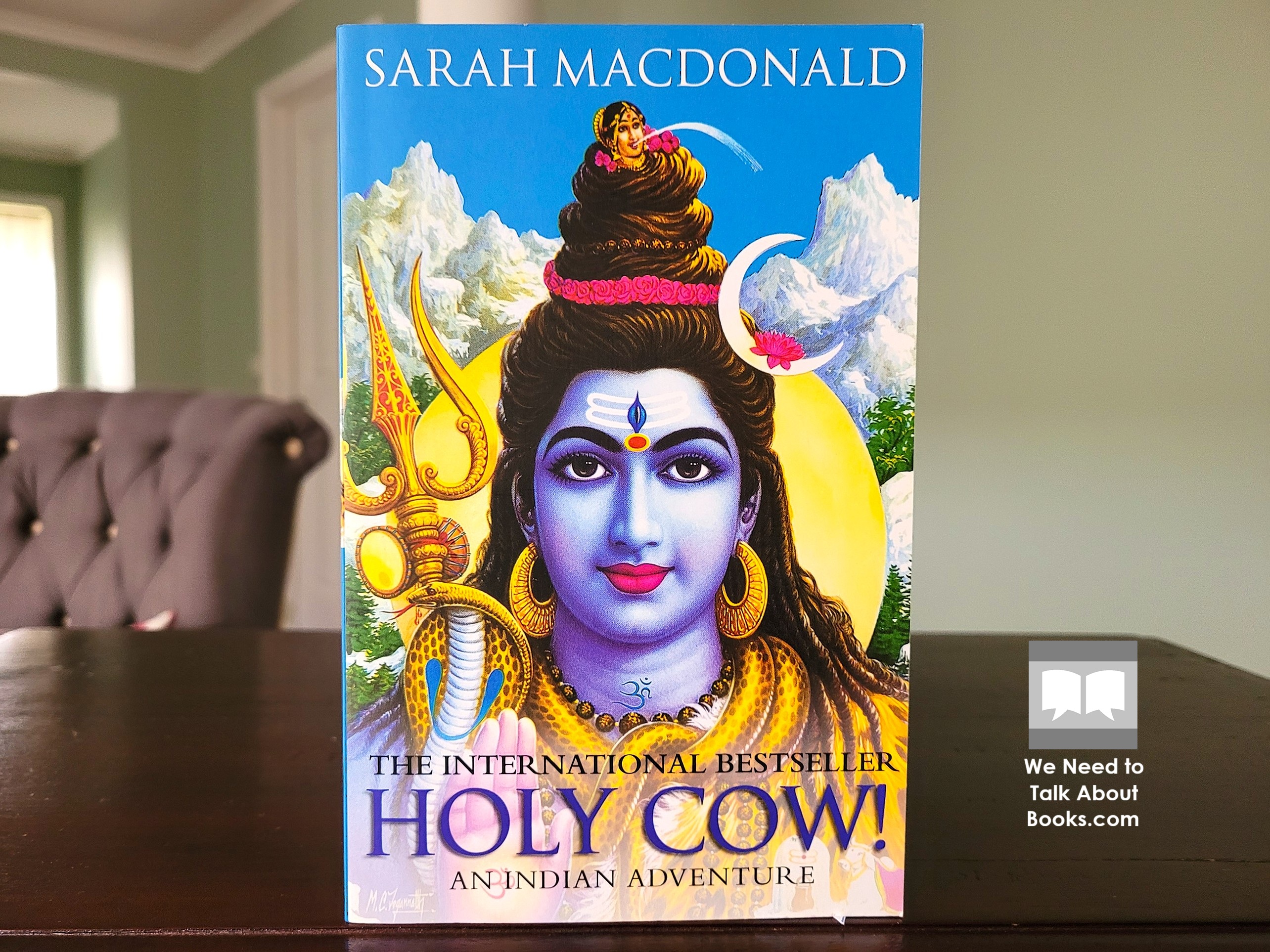

Sarah Macdonald’s Holy Cow!: An Indian Adventure is an international bestseller sighted frequently in bookstores. But I have always been dismissive. An Australian radio host is going to teach moi about India? I don’t think so.

Seeing it equally frequently in bookstores in India was a bit of a surprise. But what really changed my mind was meeting an Indian tourist guide who told me that he recommends the book to Westerners to learn something about Hinduism. I actually bought my copy in India.

Sarah’s story begins in 1988 when as a twenty-one-year-old she went on a trip to India with a friend. The overseas adventure was once a common rite of passage for many a young graduate, unfortunately it is probably beyond the finances of many today.

For Sarah, though, the trip was far from enjoyable. Leaving India she decides she hates the country with a passion. Delayed at New Delhi airport, she reluctantly indulges a cleaner who wants to read her fortune. He predicts she will return to India for love and will learn to love India.

Eleven years later, Sarah has built a successful career in radio in Australia and is engaged to be married. But, when her journalist fiancé, Johnathan, is posted to New Delhi, she sacrifices career and friends to join him.

Eleven years was long enough for Sarah to forget much of her first experience of India but on return it all starts flooding back. Sexual harassment, pollution, traffic, lack of privacy, beggars and she is not impressed by Johnathan’s flat. Then came the late night earthquake.

‘That’s it, I’ve had this country! This place is unfit for human habitation, it’s mad! Why are we here? What the hell have I done? I’ve left my job for this place! Why can’t we be normal and live where we were born? Sydney is safe. What the hell do you wear for an earthquake anyway? Jeans?’

[…]

As I hear myself rant I begin to hate myself for hating – for being so middle class and pampered and comfortable that I should now be so shell-shocked. Shaken to my core; the ground, that stable and strong bed beneath me has moved and it stirred something once rock solid within. I put my head in my hands and cry. The astrologer is right; I need a new way of living in the world if I’m to stay in this country. Perhaps this is my dance with death that he predicted.

Things get worse for Sarah. She comes down with double pneumonia, loses her hair and faces her mortality. More comes back to her of why she hated the country the first time. She also has to deal with the radical change to her lifestyle. She misses her career and struggles to adjust to household chores and cooking.

But with age comes wisdom. And the thirty-three-year-old Sarah is a little wiser than the twenty-one-year-old. She knows, for instance, that much of what she is experiencing is due to her perspective as a privileged middle-class Westerner. She also knows that all cultures have their positives and negatives and when transitioning to a new culture the negatives hit hardest and hit first. Sarah is determined to search for the positives.

Amid the manicured lawns of the embassy district cars slowed down to avoid what appears to be a branch on the road. But it’s not a branch. It’s the twisted limbs of a beggar who’s been hit by a car; he is lying in the middle of the road crying and reaching out his hands for help. We pull over and Jonathan jumps out. But as he approaches the stricken man, a bus lurches to a halt; it’s driver gets out, grabs the beggar by his arm, drags him to the gutter and dumps him, his face and abdomen bleeding from the bitumen. He’s dragged in anger, not in sympathy; human debris removed. The driver, his route now clear, jumps back on his bus and drives away.

India is the worst of humanity.

As the traffic lights, Pooja runs up to our car; She is a local beggar who knows we are the softest touch around. We’ve given her clothes, food and pay good money for the paper she sells. She has rat-tail Rastafarian hair, dimples and dirty teeth but still manages to be the most beautiful child I’ve ever seen, with a smile that would melt stone. She moves to tap on the window but sees we’re upset and hesitates. She gives me a newspaper and Pats my hand.

‘Poor memsahibs. Ap teekay hoga.’ (You will be okay.)

The pity in her liquid brown eyes is an extraordinary communication of kindness from a child who has nothing to a woman who has everything.

India is the best of humanity.

And so, Sarah embarks on a spiritual journey around India, determined to experience what the country has to offer with an open mind and heart.

What they have shown me is that India has many lessons to teach and many paths to travel to peace; I’m encouraged to find my own.

Over the rest of Holy Cow!, Sarah experiences a large variety of spiritual experiences that India has to offer. Some of these are by her own effort to seek out, some come by opportunities that cross her path. She begins with a ten-day meditation retreat at Dharamkot near Dharamsala.

She visits Amritsar to learn more about Sikhism and comes away as sceptical as Indian Sikhs are of Western approaches to the religion. The visits Kashmir and experiences the contrast of the natural beauty against the horror of terrorism and constant military presence.

I’m kind of uncomfortable about people adopting a cultural identity because they perceive their society lacks its own. I vow that if I further explore India’s smorgasbord of spirituality I won’t end up in a costume or in a cheesecloth.

She attends the Kumbh Mela – the world’s largest religious festival – where the number of attendees matches the population of Australia and an enormous amount of marijuana is consumed. There, she watches performances of scenes from the Ramayana and the Gita and enters the Ganges.

She travels to upper Dharamsala to learn about Tibetan Buddhism. Her training though is interrupted by the arrival of Jewish tourists from Israel. Learning the perspective of young Israelis for whom a national religion is enforced as well as from India’s ancient Jewish communities is an opportunity she cannot miss. Encountering the Jewish community in Mumbai also allows the opportunity to learn about the Zoroastrian community facing extinction there.

Outside the major religions, Sarah also seeks out small, local followings. One example is Amma – a woman worshipped by millions of followers in Kerala. Sarah works as a helper in Amma’s ashram and observes Amma’s devotion to her followers working fourteen hours a day without a break.

Throughout, the normally sceptical, atheistic Sarah keeps an open mind. She even experiences events she cannot explain rationally. From feeling a dose of the divine and a connection to the universal to moments of genuine euphoria. With each experience she discovers things about herself, India and these religions that she can take away, gaining new perspectives, destroying preconceptions and growing her awareness and character.

But neither can she bring herself to become a convert to any of these faiths. With each she finds dealbreakers that mean she cannot fully commit or that mean the religion simply is not a good fit for her.

The Sikhs have shown me how to be strong, the Vipassana course taught me how to calm my mind, India’s Muslims have shown me the meaning of surrender and sacrificed, and the Hindus have illustrated an infinite number of ways to the divine. But right now the Buddhist way of living attracts me most. It compliments my society’s psychological approach to individual growth and development, my desire to take control and take responsibility for my own happiness and it advocates a way of living that encourages compassion and care.

While she observes that each religion professes much open-mindedness, tolerance and leaves much to interpretation in theory, she also observes that tolerance between religions is eroding as diversity within religions also disappears. This finding is much in line with William Dalrymple’s book Nine Lives which I read shortly before Holy Cow!

Between these spiritual adventures, Sarah must return to her normal life in her New Delhi flat and face the practical challenges of the material world. It includes being taken advantage of as a foreigner contrasted with the privileges that includes and guilt that comes from being aware of it. She contemplates the Western attitude of comparing yourself to those who have more and feeling unhappy with the Indian attitude of looking at those who have less and being grateful.

How I miss Australia where destitution comes via television images, and I can press the off button. India makes me feel anything but lucky and happy. As the Vipassana hi where’s even thinner and my Sikh strength further fades, I feel increasingly dismayed and guilty. I feel guilty for not giving these women money and guilty for knowing it wouldn’t be enough. I feel guilty for being in a position where I’m privileged enough to be a giver rather than a taker and I feel guilty for wanting more than I have and taking what I do have for granted. At times I feel angry at the injustice. But most of all I feel confused and confronted. Why was I born in my safe, secure, sunny Sydney sanctuary and not in Kesroli? India accepts that I deserved it, but I can’t.

While most of Holy Cow! does what such a book should in allowing the reader to live vicariously through Sarah’s experiences, it also offers a unique perspective. While living in India a devastating earthquake strikes Afghanistan which Johnathan must leave to report on. He is still in Kabul on September 11 which puts Sarah into a moment of panic and despair. Some positive experiences, though, will also be beyond the capacity for most travellers to India to emulate. Most of us would not get to be in the audience for the Dalai Lama or get to sit with Amitabh Bachchan.

Aside from that, the only minor criticism I have is that some of her observations of India’s economy are naturally becoming outdated. Despite India’s famous unchangeable nature, much has in fact changed since this book was first published in 2002 as anyone would expect. A bigger flaw is that she offers very little about Johnathan and her relationship probably out of privacy. It means the book suffers a little because big moments such as in the immediate aftermath of September 11 are not as powerful as they should be.

Instead, the book has attracted a lot of criticism online from people who insist the book is closeminded and even racist. Scrolling through such comments I had to wonder if these readers ever read past the first few chapters or were wholly selective in what they absorbed. Contrary to their experiences I found Sarah to be very sincerely openminded to ideas and experiences that were new to her, to be willing to admit her faults and to change her mind.

That does not mean she is afraid of being critical and finding fault where she feels such opinions are worth sharing. There should be nothing wrong with that. She acknowledges the Western privilege her perspective comes from and never assumes her subjective personal experiences are to be taken as absolutes. To omit, sugar-coat, rationalise or be dishonest would be worse. I wonder if this criticism also stems from a misunderstanding of Australian culture where to be unapologetically frank is valued (though this has can be abused too).

It’s a bizarre scene – full of foreigners attempting to figure out India. I’m beginning to think it’s pointless to try. India is beyond statement, for anything you say, the opposite is also true. It’s rich and poor, spiritual and material, cruel and kind, angry but peaceful, ugly and beautiful, and smart but stupid. It’s all the extremes. India defies understanding, and for once, for me, that’s okay. In Australia, in my small pocket of my own isolated country, I felt like I understood my world and myself, but now, I’m actually embracing not knowing and I’m questioning much of what I thought I did know. I kind of like being confused, wrestling with contradictions, and not having to wrap up issues in a minute before a news break. […] India is in some ways like a fun hall of mirrors where I can see both sides of each contradiction sharply and there’s no easy escape to understanding.

What’s more, India’s extremes are endlessly confronting.

As I said at the beginning, I had my own prejudices to overcome to bring myself to read this book. In the end I am glad I did. Although feeling a tinge of jealousy at the experiences Sarah has had in a land I have a complicated and affectionate relationship with, I am grateful Sarah chose to share her adventures and that the book did eventually find its way to me.