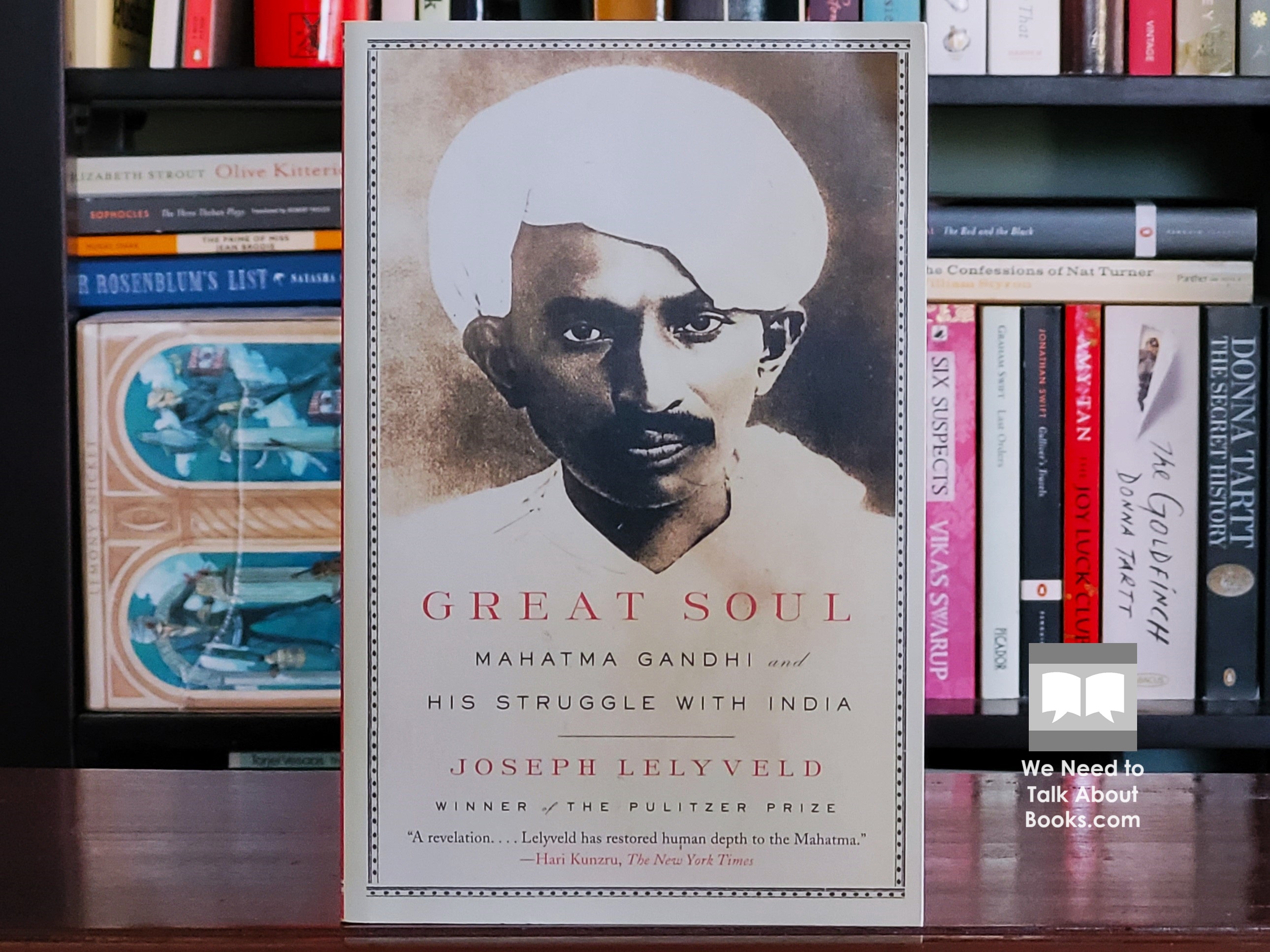

Joseph Lelyveld’s book on Gandhi, Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggles with India was controversial when first published, partly for trivial reasons. More importantly, it sought to separate the man from the myth and critique his achievements in a way that readers familiar with the myth and unfamiliar with the history might find provocative. Though not without its flaws, there is considerable value to be gained from Lelyveld’s take on one of history’s most influential persons. One whose successes and failures, Lelyveld argues, are still having an impact today.

Joseph Lelyveld begins his book on Gandhi with a provocative question – was Gandhi a failure? He argues that by Gandhi’s own standards he was. Compared to the goals Gandhi set himself to achieve, Bihar is still one of India’s poorest states; landlord’s and the wealthy classes still wield much power; untouchability has not been removed; Hindus and Muslims are not merely still divided, they now live in three different countries to British India. The reverence the world holds for Gandhi remains but, according to Lelyveld, it does not match his achievements. However generous we may want to be, whatever we might ascribe to Gandhi, Lelyveld argues we must assess according to the man’s own standards.

Lelyveld’s book is not really a biography. For example, he skips past Gandhi’s family history and his youth before he first travels to South Africa in 1893.

This isn’t intended to be a retelling of the standard Gandhi narrative. I merely touch on or leave out crucial periods and episodes – Gandhi’s childhood in the feudal Kathiawad region of Gujarat, his coming-of-age and nearly three formative years in London, his later interactions with British officials on three continents, the political ins and outs of the movement, the details and context of his seventeen fasts – in order to hew in this essay to specific narrative lines I’ve chosen. These have to do with Gandhi the social reformer, with his evolving sense of his constituency and social vision, a narrative that’s usually subordinated to that of the struggle for independence.

This raises an important question of whether Gandhi’s life can really be critically assessed without taking a broad view of his life, relationships, cultural and historical context. Despite the non-biographical limitation, it largely proceeds in chronological order, not necessarily by the main areas Lelyveld is critiquing. Here, I will not detail the biographical aspects of Lelyveld’s book but its central aim of assessing Gandhi’s ideas and achievements.

Gandhi as an Advocate For the Poor

Most people who know the basics of Gandhi’s life (or at least know the surface level from sources such as David Attenborough’s film) know that he first came to prominence not in India but in South Africa. Those who have taken the trouble to know Gandhi’s life in more detail will not be surprised to learn that for most of the time his was in South Africa, Gandhi was an advocate for the rights of wealthy, mostly Muslim, Indian merchants who wanted greater equality with the ruling white South Africans. However, the majority of Indians in South Africa were poor indentured labourers living and working in conditions little above slavery.

Lelyveld shows that Gandhi was largely apart from this lower class of Indians for the duration of his time in South Africa. For most of his time there, he did not engage with them and spoke condescendingly to them. Lelyveld finds little in Gandhi’s words and less in his actions that suggest an interest in the plight of the poor.

Gandhi’s real attitude to the indentured in this period is made plain by the arguments he advanced on the first of his losing causes in South Africa: that of protecting the voting rights of literate, propertied Indians. Such Indians, he wrote in December that year, “have no wish to see ignorant Indians who cannot possibly be expected to understand the value of a vote being placed on the voters list.”

[…] Here again he’s plainly saying that “free Indians” are members of the community; Indian indentured labourers are not. So while he has told us in the pages of the Autobiography that he was now recognised as “a friend,” a man who knew their “joys and sorrows,” his claim to have “got into closer touch” with the indentured with whom he served on the fringes of Boer War battlefields rings a little hollow.

But towards the end of his time in South Africa, opportunities emerge when miners go on strike and when a new law says non-Christian marriages will not be recognised.

Becoming an advocate for the poor was no minor turn for Gandhi because it meant potentially alienating himself from the wealthy who were his earliest supporters as well as his patrons. Lelyveld questions what brought about this change in Gandhi. He looks at the influence of those around Gandhi, the works Gandhi was reading that was impacted his thinking, the criticisms he received from opposition that moved the needle and made Gandhi into a leader for the underclasses.

It’s a picture to fix in the mind: Gandhi, in the thick of his struggle, feeding his followers – described by another reporter on the scene as “consisting mostly of the very lowest castes of Hindus,” plus “the merest smattering of Mohammedans”- with his own hands. That a certain proportion of the strikers (maybe 20 percent, maybe more) were considered untouchable in the Tamil villages from which they originally hailed is no longer, for Gandhi, something to be remarked upon. In his own mind, feeding them one by one in this way is basic logistics, not a display of sanctity. But for however many hundreds or thousands who received their food directly from his hands, he set a new standard for Indian leadership, for political leadership anywhere.

Lelyveld endorses the controversial opinion of Nobel Prize Winning writer VS Naipaul, that when Gandhi returned to India he viewed it with a foreigner’s eyes and was appalled by the inequality and sanitation. By 1921, Gandhi was making speeches to audiences of tens of thousands but Lelyveld argues his actual words had little impact.

At times Gandhi seems aware that his message is not getting through. Politicians either fail to enact his policies or they undersell them. The public do not act on his words. Even his close followers who do put his policies into deeds find that change is insurmountable. A disappointment Gandhi has to repeatedly endure is that others will happily take his service without feeling obliged to do their part.

Gandhi as an Advocate For the Untouchable

On the issue of untouchability, Lelyveld contrasts Gandhi with two other contemporary claimants to leadership on the issue – Swami Shraddhanand (aka Mahatma Munshi Ram Vij) and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. He puts a focus on the issue of the Vaikom Temple – a temple that untouchables were not permitted to approach and became a centre for the issue and a target for protests.

Lelveld struggles to reconcile Gandhi’s views on the issue and it is difficult to disagree. To my reading Gandhi’s rationalisations for his positions seem inconsistent, contradictory and hypocritical. If there is an explanation it may be that Gandhi was being deliberately ambiguous because he knew was cornered on the issue. Ambedkar believed Gandhi’s internal conflict lay in trying to be both a religious and a political leader and I am inclined to agree.

What’s at issue for him in Vaikom is a question that will hover over his leadership for the rest of his life: could he continue to function as a national leader, or has he been driven by the diversity and complexity of India, with all the clashing aspiration’s arising from its communal and caste divisions, to define himself as leader of the Hindus? Could he simultaneously lead a struggle for independence and a struggle for social justice if that meant taking on orthodox high-caste Hindus, which would inevitably strain and possibly splinter his movement? Behind that question lurked an even more unsettling and long-lasting one, a question still debated by Dalits and Indian social reformers: granted that Gandhi did much to make the practise of untouchability disreputable among modernising Indians, what exactly was he prepared to do for the untouchables themselves beyond preaching to their oppressors? It was such questions that – acting from afar – he’d been trying to finesse at Vaikom, with the result that this first use of satyagraha against untouchability was now in danger of languishing.

Lelveld argues that the impact of Gandhi’s failure on the issue is still felt in India today. He is not held in as high regard in the south as in the north. India has experienced a revival of Buddhism from conversions of untouchables. And Ambedkar, not Gandhi, is their hero.

In their ambiguity, his own responses were at the time unsatisfying and still are. Outside Kerala, Gandhi’s role in the Vaikom satyagraha is most often interpreted uncritically as a fulfilment of his values: his unswerving opposition to untouchability, his adherence to nonviolence. Inside Kerala, where this history is better known, it’s usually seen as having shown up a disguised but unmistakable attachment on his part to the caste system. Neither view is convincing. What really shows here is the difficulty of being Gandhi, of balancing his various goals, and, more particularly, the difficulty of social change in India, of taking down untouchability without cleaving his movement and sowing the “chaos and confusion” he feared.

Gandhi and Hindu-Muslim Unity

That Gandhi’s goal of Hindu-Muslim unity failed is easily apparent to anyone who looks at a map of Asia. Lelyveld tracks the evolution of the issue in Gandhi’s time. Initially on return from South Africa Gandhi enjoyed considerable support from India’s Muslims. His work in South Africa gave him experience and credibility no non-Muslim Indian leader had. In addition, Gandhi supported their wish for the reestablishment of a Khalifate.

But Lelyveld argues this support was a façade doomed to unravel in the future. Gandhi set expectations that could not be met and made unequal demands of each side. As the years went by and faith in Gandhi deteriorated, both Muslims and orthodox Hindus found their own leaders distinct from Gandhi and his methods.

The [Swami Shraddhanand’s] political vicissitudes are worth dwelling on for the light they shed on Gandhi’s dilemma. The younger Mahatma, now in his fifties and fully fledged as a national leader, usually spoke as if his campaigns for unity between Hindus and Muslims and for basic rights and justice for the tens of millions of oppressed untouchables were mutually reinforcing, the warp and woof of swaraj. In fact, they were often in conflict, not merely for his attention or primacy in the movement he led, but at a local level where proselytisers and religious reformers battled for souls. And, truth to tell, neither cause – that of Hindu-Muslim unity nor justice for untouchables – had much appeal to caste Hindus, especially rural caste Hindus, who were the backbone of the movement Gandhi and his lieutenants were building. His political revival may have articulated the nation’s highest aspirations, but examined more closely at a regional or local level, it turned out to be a fragile coalition of competing, frequently clashing communal interests.

Giving Gandhi Credit

Reading the above you may think Lelyveld’s book is just a hatchet job of Gandhi, eviscerating him for where he came up short. But this just reflects my interest in the book’s material. Most of what I had read previously of Gandhi was fawning, subjective or otherwise flawed. I welcomed an approach that is more empirical and critical.

If simply attacking Gandhi was his aim, Lelyveld could have gone further. I am surprised no mention is made of the contrast of Gandhi’s rejection of modern medicine except when he needs surgery for haemorrhoids or appendicitis.

To say that Gandhi wasn’t absolutely consistent isn’t to convict him of hypocrisy; It’s to acknowledge that he was a political leader preoccupied with the task of building a nation, or sometimes just holding it together.

But in fact, Lelyveld’s book also gives Gandhi much credit where it is due. Though Lelyveld says it took time for Gandhi to come around to being an advocate for the poor and it does not seem his words or methods had great impact, what did resonate was that Gandhi cared for them in a new and unusual way. Lelyveld also argues that Gandhi distinguishes himself for his commitment to their cause, for his constant attention to it, for insisting that solutions be found where the poor live and that these are larger points.

When the bare narrative of this effort to achieve “oneness” with India’s poor is laid out, it can appear either futile or desperate. It’s the effort of the Mahatma to remain true to his vision of swaraj for the dumb millions, despite all that he has learned, or perhaps senses he has yet to learn, about village India. Yet from a distance of more than seven decades, what stands out is the commitment rather than the futility. He could easily have retired to a mansion belonging to one of his millionaire supporters and there directed the national movement from on high; no one would have asked why he wasn’t living like a peasant. In his tireless, pertinacious way in the village to which he attached himself instead, he was doing more than tilting at windmills. Once again Gandhi was refusing to avert his eyes from a suffering India that seemed largely to have escaped the notice of most educated Indians swept up in the movement he’d been leading.

Lelyveld even makes the point that “Gandhian economics” – easily written off as oversimplistic, utopian and naïve – have parallels with modern strategies for alleviating rural poverty and indebtedness.

And though Lelyveld says at the outset that we should judge Gandhi by his own standards, he does question this approach and the standards themselves. Were his goals even achievable? Don’t all political and religious leaders set unachievable goals? Would other leaders – Muhammad Ali Jinnah or Jawaharlal Nehru – have done better?

Gandhi and Kallenbach

Before we finish, there is a somewhat trivial issue to address. When Lelyveld’s book was first published, it attracted a lot of attention and contempt for what many interpreted as an insinuation that Gadhi had a homosexual affair. While in South Africa, Gandhi made a close friendship with Hermann Kallenbach a white Jewish German immigrant, an architect, a bodybuilder and a lifelong bachelor.

Lelyveld describes their relationship as ambiguous and intimate. They teasingly refer to their letters to each other as ‘love letters’. At one point the married Gandhi leaves the home he shares with his wife to live with Kallenbach where they could experiment with their ideas of vegetarianism, celibacy, rejecting comfort, embracing poverty.

Lelyveld admits he does not know what to make of this. Naturally any insinuation provoked an outsized reaction in India. The book was partly banned giving further credence to the reputation of India’s public and government for being overly sensitive to the point of insecure. Other historians provided a calmer, more reasoned response. They argue that Lelyveld simply misunderstands the characters of Gandhi and Kallenbach and their relationship. An understandable confusion given the narrow sources of material used by Lelyveld.

One of those historians is Ramachandra Guha. Writing in 2011, Guha defends Lelyveld’s book against being banned without defending his conclusions, saying “The answer to a book is another book – not a ban”.

Placing Lelyveld’s Great Soul

Readers will be aware that Guha would have had such a book in mind when he wrote his response. His Gandhi Before India (2013) and Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World (2014) would have been nearing completion at the time.

In fact, one of the difficulties I had in writing this review of Lelyveld’s book is the fact that I have already read Guha’s excellent Gandhi Before India and did not want what I have learned there to affect this review. However, it does help to place Lelyveld’s in context. As I have said, early biographies of Gandhi were flawed; often giving in to the saintly myth around him. Lelyveld’s book is a welcome break from that. But returning to the question I asked earlier – of whether it was possible to truly critique Gandhi’s achievements without taking a broad and deep look at his life and historical context – I would say that it is not. Comparing Lelyveld’s book to Guha’s extensively researched one makes that fact and the weaknesses of Lelyveld’s book clear.

Given the apparent superiority of Guha’s take, should you read Lelyveld’s book? I would say it depends. If like me you have more than a small interest in the subject, I would say it is worth your time. Lelyveld asks important questions about the perception of Gandhi against the reality. Even if his answers to these questions are limited, they are questions worth considering and it has a place in the evolution of interpretations of Gandhi. If your interest is not so extensive that you are willing to read multiple books on Gandhi, then perhaps fast forwarding to Guha’s books is best.

Today, people are less daunted to challenge the myth of Gandhi than they may have been when Lelyveld’s book was published. Gandhi has become something of a tall poppy that some seem to enjoy cutting down. A common attack is to point out Gandhi’s racism towards black South Africans. It is an issue that both Lelyveld and Guha address in their books. I have chosen not to discuss it here, leaving it for when I review Guha’s book. But the frequency with which this over-simplified jab is thrust speaks both to the unsophisticated point-scoring nature of today’s public discourse as well as to the more reasonable fact that Gandhi’s legacy has become more open to analysis and critique.

Overall, I enjoyed Lelyveld’s book and am glad to have read it. In removing Gandhi’s saintly garb he has humanised his subject. He has shown a man who was altruistic yet also ambitious and self-serving; humble yet susceptible to his own myth; was flawed, naïve and made errors yet was still responsive and evolving. I have probably over-emphasised his criticisms in this review but the real outcome of this book is to demythologise Gandhi without discrediting his real impact or achievements. In this Lelyveld has succeeded admirably.

Thank you for this review.

You make a point about “unsophisticated point-scoring nature of today’s public discourse” and I think this is true of much current discourse about decolonisation. The British are simplistically blamed for partition, when Lelyveld’s book seems to show that there was deep seated religious hostility that even the charismatic Gandhi could not overcome.

LikeLike