The Persian Boy is Mary Renault’s second part to her Alexander Trilogy. Told from the point of view of Bagoas – a servant to the Persian King Darius and, following his fall, to the Macedonian King Alexander, it is a tale of the brutal realities of war, conquest and power struggles in an ancient world whose codes of morality, politics and sexuality may seem alien to us in the twenty-first century. But such is the skill of Renault’s writing that she makes brings this ancient world to life and seduces us into comprehension.

Lest anyone should suppose I am a son of nobody, sold off by some peasant father in a drought year, I may say our line is an old one, though it ends with me. My father was Artembares, son or Araxis, of the Pasargadai, Kyros’ old royal tribe. Three of our family fought for him, when he set the Persians over the Medes. We held our land over eight generations, in the hills above Susa. I was ten years old, and learning a warrior’s skills, when I was taken away.

Our hill-fort was as old as our family, weathered-in with the rocks, its watch-tower built up against a crag. From there my father used to show me the river winding through the green plain to Susa, city of lilies. He pointed out the Palace, shining on its broad terrace, and promised I should be presented, when I was sixteen.

That was in King Ochos’ day. We survived his reign, though he was a great killer. It was through keeping faith with his young son Arses, against Bagoas the Vizier, that my father died.

At my age, I might have heard less of the business, if the Vizier had not borne my name. It is common enough in Persia; but being the only son and much beloved, I found it so strange to hear it pronounced with loathing, that each time my ears pricked up.

So begins Bagoas’ telling of his life story. The ‘business’ he writes of overhearing as a child was the involvement of the Vizier who shares his name in the power struggles at the top of the Persian Empire. King Ochos was trying to trim back the Vizier’s power when the King died suddenly. Poison was suspected. The brothers of Ochos’ heir, Arses, died too, putting the Vizier in a position where he could rule through the young King Arses. Arses’ reign is not a long one. He and his sons are soon killed and the Vizier becomes the effective ruler of Persia.

It is around this time that Bagoas’ father was called away but is betrayed and murdered. Soldiers take their hill-fort. In horrific scenes, Bagoas witnesses his mother leaping to her death rather than be raped and murdered by the invaders. In mid-plunge their eyes meet. She had assumed he was already dead when she jumped and thought she had no reason to live. The look on her face has haunted him ever since.

But worse was to come for Bagoas.

He is sold to a dealer who gelds him. He describes the horrific pain of a process many do not survive. Now a eunuch, Bagoas is sold to a gem trader to be a new servant for his wife.

The new King of Persia is Darius. Known for his height, elegance and beauty as well as his gracious and mild temperament, Darius outwits the Vizier Bagoas which leads to the Vizier’s death.

Early into his reign, news comes of trouble on Persia’s western borders. The trouble-makers are blue-painted, red-haired barbarians called ‘Macedonians’. But their King is dead, assassinated in a public spectacle, and his heir is young. It does not seem worth any concern. But now the young Macedonian King has crossed into Asia and, one-by-one, the Greek cities of Asia have fallen to him and yet he does not seem content. Darius and his entire court must depart to deal with the menace.

It soon becomes apparent that dealing with the invaders is no simple matter. King and court have been out of the city a long time, severely damaging business including Bagoas’ master’s jewellery trade. Soon Bagoas is being loaned to men for sex. It becomes a daily thing. Most of whom are unpleasant, some violent but some kind.

News then reaches the city of Darius’ defeat to the invaders at Issos. The King is said to have fled the field early in the battle, abandoning his own family. Rumours that the barbarians have given protection to the captured royal family are not credited.

They said that at Issos Nabarzanes had fought a great battle, though the King’s choice of ground had been a blunder. The cavalry had charged when the rest were faltering, taken on the Macedonian horse, and hoped to turn the tide; then the King had fled, among the first to leave the battle. With that came rout. No one can fly and fight; but the pursuer can still strike. There had been a great slaughter; they blamed the King.

With the court back in the city, Bagoas, now thirteen years old, is loaned to men of the higher classes who want him for more than just sex. Soon he is sold. His new master trains him in serving and dressing. He learns to ride a horse, play music and sing. He has no idea why. He still hates the sex, which is painful to him, but he is promised it will get better. It is only when he is shown how to correctly prostrate himself that he realises the unimaginable – he is being trained to serve the King.

Bagoas begins work in Darius’ palace and is soon serving the King personally, including in the bed chamber. Darius, who remembers Bagoas’ father favours him with a horse, a slave, a nice room and expensive gifts.

But the barbarians continue their march forward, taking cities, holding the King’s family hostage and rejecting offers of peace. Soon, the King is again preparing for battle.

The King was the King; He could not have believed the sacred state could be altered, except by death. Disaster after disaster, failure on failure, shame on shame; friend after friend turned traitor; his troops, to whom he should have been godlike, creeping off like thieves every night; Alexander approaching, the dreaded enemy; and, still unknown, the real peril at his elbow. And to trust in, whom? We few, who for the use of kings had been made into less than men; and two thousand soldiers serving for hire, still faithful not for love of him, but to keep their pride.

As we marched, the road rising through bare uplands, I suppose there was no one in the household who was not thinking, and what will become of me? We were only human. Boubakes thought, perhaps, of want, or a dreary life in some low- rank harem. But I had only one skill, I had only known one employment. I remembered slavery in Susa. I was no longer too young to find the means of dying. But I wished to live.

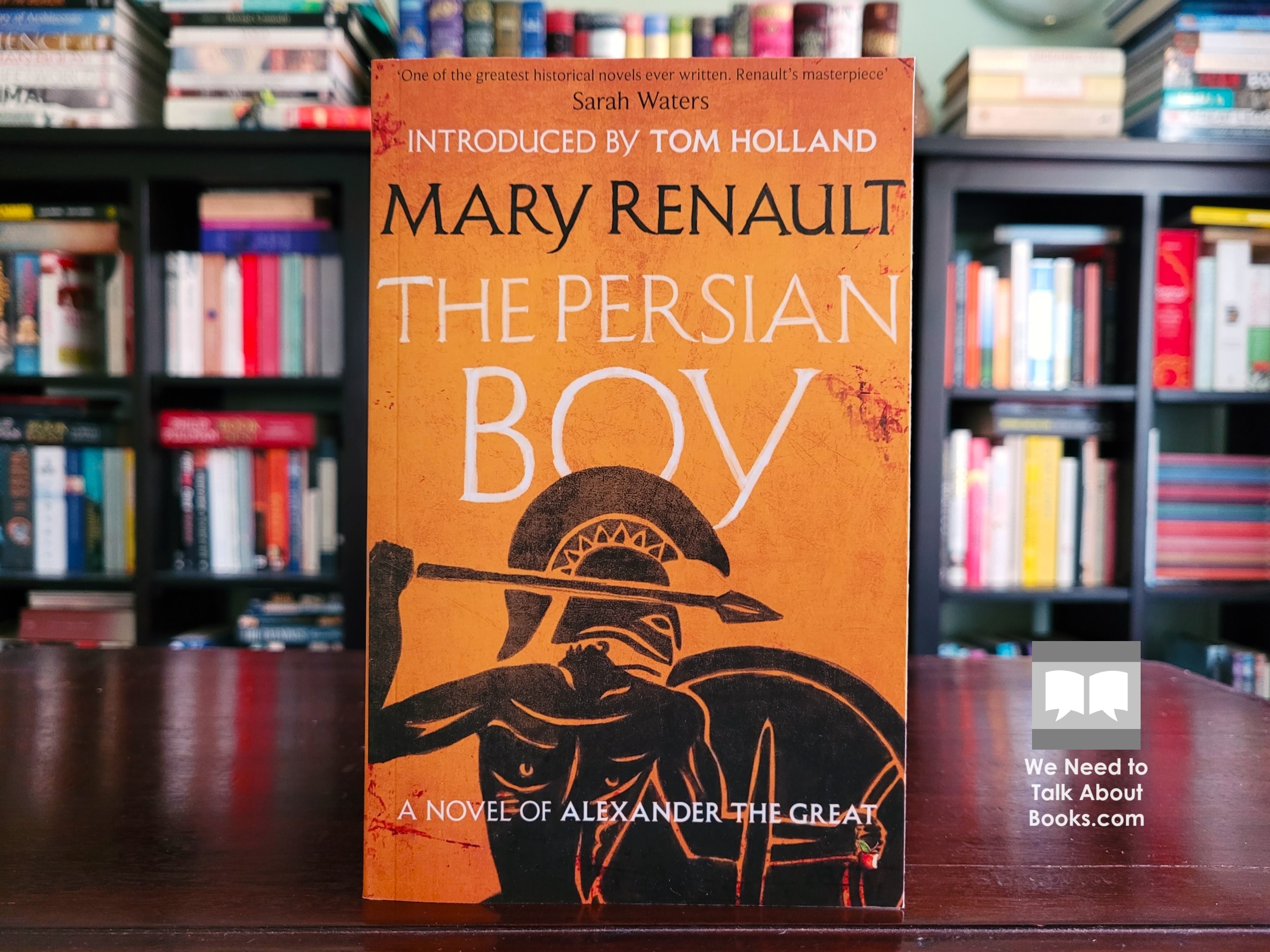

The Persian Boy is the second part of Mary Renault’s Alexander Trilogy after her Booker Prize nominated Fire From Heaven.

The Persian Boy is told in the first person from Bagoas’ perspective. He tells his life story years after the events, from the relative safety and comfort of Egypt where Ptolemy, Alexander’s former general, has given him a home. As a courtesan and member of the royal household to both Persian King Darius and Macedonian King Alexander, Bagoas has a front row seat to one of the most turbulent periods of the ancient near east. He is an internal witness to the fall of the Achaemenid Empire and the struggle of Alexander to establish his vision of a successor empire.

The Persians said, ‘Bagoas the eunuch is Alexander’s dog. He will feed from no other hand; let him be.’ Macedonians said, ‘Watch out for the Persian boy; He tells Alexander everything.’

Bagoas is more than a passive observer, however. His life is in jeopardy more than once and he finds he must rely on his acquired arts to assure his survival. More than that, he finds it necessary to use his skills to not merely give his new master comfort away from his troubles, but to influence events in his master’s favour. Especially a master who, having achieved his life’s goals so early, finds himself unsure about what to do next.

I enjoyed The Persian Boy more than Fire From Heaven. I found Fire From Heaven did not fit a familiar archetype of a coming-of-age story and was a little unsatisfying because of it. Though a different type of story, The Persian Boy feels a bit more complete in that regard and therefore more satisfying. It is also a longer and more complex story.

Much of that complexity comes directly from Alexander’s leadership dilemmas and the intrigues against his wishes and actions. He faces difficulty in gaining support for his vision, in managing the expectations and egos of his men and finding a place for the Persian leaders he is now master of. Sometimes these lead to violent ends with Alexander failing to live by his own principles.

In six previous novels by Mary Renault that I have read and reviewed, I have already said much of her reputation as a superb historical novelist and her inspiration to others. The Persian Boy offers more evidence in her favour. As you might expect, she gets the broad perspective of this period of history, with its empire-overturning war, well enough to satisfy those with keen eyes for history. However, she does not go into great detail with the warfare. I suspect that it would not be a strength of hers and her narrator, chosen for the strength of his perspective, would conveniently not have been a likely close witness.

So now I saw what I’d not seen all through Baktria; the herd of wailing woman and children, driven into camp like cattle, the spoils of war. All the men were dead.

It happened everywhere. Greeks do it to other Greeks. My own father must have done it, in Ochos’ wars; though Ochos would never have given such people a first chance. However, this was the first time for me.

Alexander did not mean to drag along this horde of women; he was planning a new city here, and they would give the settlers wives. But meantime, soldiers short of a bedmate-slave were getting their pick. A woman would be led away; sometimes young children with wet dirty faces would stumble after, sobbing or screaming, to be cared for when her new master gave her time. Some of the young girls could scarcely walk; their bloodstained skirts showed why. I thought of my three sisters, whom I’d long managed to forget.

This was the slag of the fire when the bright flame had passed. He knew what he was born to do; the God had told him. All those who helped, he would receive like kindred. If he was checked, he did whatever was necessary; then went on his way, his eyes on the fire he followed.

Where her strengths do show through is in her knowledge of the cultures of Persia and Macedonia and in how they clash once the latter conquers the former. It surfaces in several ways in the novel and is a major driver of the conflict in its second half if not also being a major theme.

I had heard already of their barbarous way with wine, bringing it in with the meat. But nobody had prepared me for the freedom of speech the King permitted. They called him Alexander, without title, like one of themselves: they laughed aloud in his presence, and far from rebuking them he joined in. The best you could say was that when he spoke, nobody interrupted him. They fought over their campaign like soldiers with their captain; once one said, ‘No, Alexander, that was the day before,’ and even for this received no punishment, they just argued it out. However, I thought, does he get them to obey in battle?

Renault’s Author’s Note also provides some insights into her process regarding historical accuracy. For example, she mentions the impossibility of including all major events of this period; what we know of Alexander’s sex life from sources and what is unlikely; she shares sources of Bagoas and addresses misconceptions about eunuchs. She also discusses issues around the reliability of sources, understanding their political motives, the morality of the time and interpreting them with scepticism and erring towards the more probable.

Historian Tom Holland, author of Persian Fire among other books on the ancient world, wrote the Introduction to this edition of the Alexander Trilogy. He too has a high regard for her writing and, as evidence, points to how she is able to convince the reader of her interpretation of Alexander’s personality.

So detailed and finally textured is her portrayal of Alexander’s world, and so credible her evocation of his psychology, that the reader rarely pauses to take him on anything other than Renault’s own terms. ‘In grief more than enjoy, man longs to know that the universe turns around him.’ For most, such a yearning breeds only illusion; but with Alexander, Renault could explore a hero who had indeed moulded the world to his own ambitions, and made himself its pivot. The intoxicating pleasure of her trilogy is that it enables us to share in the glory and potency of such a man. ‘In his presence,’ declares Bagoas in The Persian Boy, ‘I felt more beautiful.’ all readers who find themselves seduced by Renault’s fictionalisation of Alexander are liable to feel much the same.

From the Introduction

He also writes that a common element of her novels is to include characters who blur the gender divide, perhaps in response to the maintenance by the Greeks of a strong contrast between masculine and feminine. Bagoas is the best example of such a character.

Indeed, so formidable is [Bagoas’] commitment to self- invention that marks him as both the most original of Renault’s characters, and the most paradigmatic. Striking a balance between the twin ideals of hardiness and beauty, Bagoas is tough enough to accompany Alexander on even the most demanding of his campaigns, yet practised enough in the arts of the bedchamber to satisfy him more fully than any woman. Men too, even Alexander himself, are tempted by the scope for reinvention offered by a spot of gender-bending. Smooth-cheeked, in pointed contrast to his hirsute father, and rumoured to possessing ‘a natural fragrance’, the attributes of femininity only served to enhance the potency of Alexander’s world-conquering charisma.

From the Introduction

There is no shortage of readers who enjoy historical fiction. For that reason alone, Mary Renault should be on your radar. In addition, there is no shortage of enthusiasts for experiencing certain historical figures and periods brought to life – Caesar, Napoleon, Tudors, World Wars, etc. Renault’s Alexander Trilogy therefore rests in the intersection of these interests and should continue to be enjoyed by those who can find her work. I am glad I have made the effort. Of the seven of Mary Renault’s novel’s that I have read, I found The Persian Boy to be one of her best ones. And if you enjoy it too you will find more to enjoy in her other works.