Even for an historical novelist of the calibre of Mary Renault, what she embarks on in Fire From Heaven is extremely ambitious. A coming-of-age tale of one of the most well-known and scrutinised figures in history, yet set in a period of his life we know very little about.

A boy, almost five years old is woken in the night by the feeling of something moving against his body. He looks down and sees a snake is in his bed. He checks the pattern on the snake’s body and sees that it is not dangerous. It must be his mother’s pet, Glaukos. He resolves to return it to his mother.

To reach his mother’s room he must slip past two palace guards who would otherwise stop him and return him to his room. This he knows how to do. The palace is not quite silent. There is the echo of drunken, raucous men’s voices. His father has been drinking with his men.

Leaving his room, he works his way to his mother’s bedroom. Past a large bronze statue of Apollo standing on a plinth of green marble. Up a short set of stairs, the walls painted with trees and birds. Agis is the man standing guard in from of the royal bed chamber with its door of polished wood and a great ring handle inside a lion’s mouth. Agis is in his parade uniform. His helmet has a crest of red and white horsehair and hinged cheek flaps embossed with lions. His painted shield is on his shoulder, not to be put down until the king was safe in bed. His spear in seven feet long.

Fortunately for the boy Agis has been drinking a little too and needs to urinate. He walks away from the door to go behind the statue of a sitting lion and this gives the boy the chance to enter to bedroom.

Inside, the room smells of bath oils, incense and something his mother burns for magic. On one wall is a mural depicting the fall of Troy with life-size figures. His mother’s bed has legs inlaid with ivory, tortoise shell and ends in carved lion’s feet.

He wakes her. She thanks him for bringing the snake, but it is not her pet. She tells him it is his daimon and he names it Tyche.

The boy’s father enters the room. A large imposing man, he has come expecting sex and is angry at his wife’s denial and angrier still at the presence of the boy. Husband and wife get into a spiteful argument, over sex and the boy’s education. He calls her a barbarian and they hurl accusations at each other over their origins and upbringings.

The boy has a strong oedipal complex; he hates his father and wishes he could marry his mother. The boy is thrown out of the room by his father and comforted by the guard Agis who takes him back to his room.

On another day, envoys from Persia have come to meet his father who is late to their meeting as he is out drilling with his troops, something the Persians think is beneath a great king. The boy goes to meet them himself. He asks them about the Persian army and the envoys boast about its size and the breadth of their great empire. The boy is not impressed and, showing knowledge beyond his years, wonders if the size and diversity of the empire is a handicap in war. The delay in assembling an overwhelming army and the problems created by different weapons and languages are weaknesses that could be exploited.

The Persians are equally unimpressed by the boy’s arguments but happily and patronisingly humour him. The Persians believe in learning the lessons of other’s victories, while the boy and his father believe in learning from other’s defeats.

Later, the boy’s father grills his son on his meeting with the Persians and asks his thoughts on matters. As much animosity as there is between father and son, when it comes to matters of history, culture, war and its aftermath – kings, battles, weapons, training, supplies, tactics, strategy, treaties, alliances, governance – the two share a mutual passion and a mutual respect. The boy is saddened by what his father shares of the history of their forefathers infighting, betrayal and cowardice in the face of the all-conquering Persians and shares his wish that they might live to see the rise of a leader who could reverse these losses.

‘So when King Xerxes came, Alexandros fought him?’

Philip shook his head. ‘He was King by then. He knew he could do nothing. He had to lead his men in Xerxes’ train with the other satraps. But before the great battle at Plataia, he rode over himself, by night, to tell the Greeks the Persian dispositions. He probably saved the day.’

The boy’s face had fallen. He frowned with distaste. Presently he said, ‘Well, he was clever. But I’d rather have fought a battle.’

‘Would you so?’ said Philip grinning. ‘So would I. If we live, who knows?’ He rose from the bench, brushing down his well-whitened robe with its purple edge. ‘In my grandfather’s time, the Spartans, to secure their power over the south, made treaty of alliance with the Great King. His price was the Greek cities of Asia, which till then were free. No one has yet lifted that black shame from the face of Hellas. None of the states would stand up to Artaxerxes and the Spartans both together. And I tell you this: the cities will not be freed, till the Greeks are ready to follow a single war-leader. Dionysios of Syracuse might have been the man; But he had enough with the Carthaginian’s, and his son is a fool who has lost everything. But the man will come. Well, if we live we shall see.’

On another night, not wanting to sleep, he sneaks out again. He goes to the shrine of Herakles where he sees people, including his mother, gathering for a sacrifice to Dionysus. He watches the sacrifice of a goat and the women dancing. Having some wine, he joins in, building to a point of religious ecstasy where he imagines he can see Dionysus dancing a path all over the known world. His mother pulls him away, wraps him in a blanket and puts him on a mat where he falls asleep.

I am sure that the above sharing of events from the first chapter of Fire From Heaven it is clear to all that what we have here is a telling of the childhood of Alexander the Great, part one of Mary Renault’s Alexander Trilogy.

As the sixth novel I have read by Mary Renault, there were some things I already knew to expect. Considered one of the great writers of the historical fiction genre, it is no surprise that her knowledge of the history is extensive, impressive and cleverly used. The book is infused with little details that bring this world to life. Though my synopsis is a poor imitation, right from the beginning of the novel she shows herself to be a great scene-setter.

In particular, her descriptive writing is very sensorial creating an immersive experience for the reader. One part of the novel where her technique particularly impressed me is where she used descriptions of the sights, sounds and smells to evoke the gruesome realities of life in an army camp, of battle and of its aftermath.

Some of this history is quite complex. This is especially the case for those characters such as Mentor, Memnon and others who within their lifetimes went from being leaders of Greek city states in Asia Minor who fought against invading Persians, lost and were forced into exile, were forgiven by Persia and given new positions of power and then found themselves fighting for Persia against their fellow Greeks. Again, Renault shows her skill in handling the complexity of the events of this era without burdening the reader with any of it.

Naturally, the passage of time means that some of her interpretations of history have come into criticism. This is less true of the knowledge of events or physical history she displays, more about the characterisation of historical people including Alexander. Her writing mostly reflects established thinking of the time which has since moved on and needn’t trouble the reader greatly here.

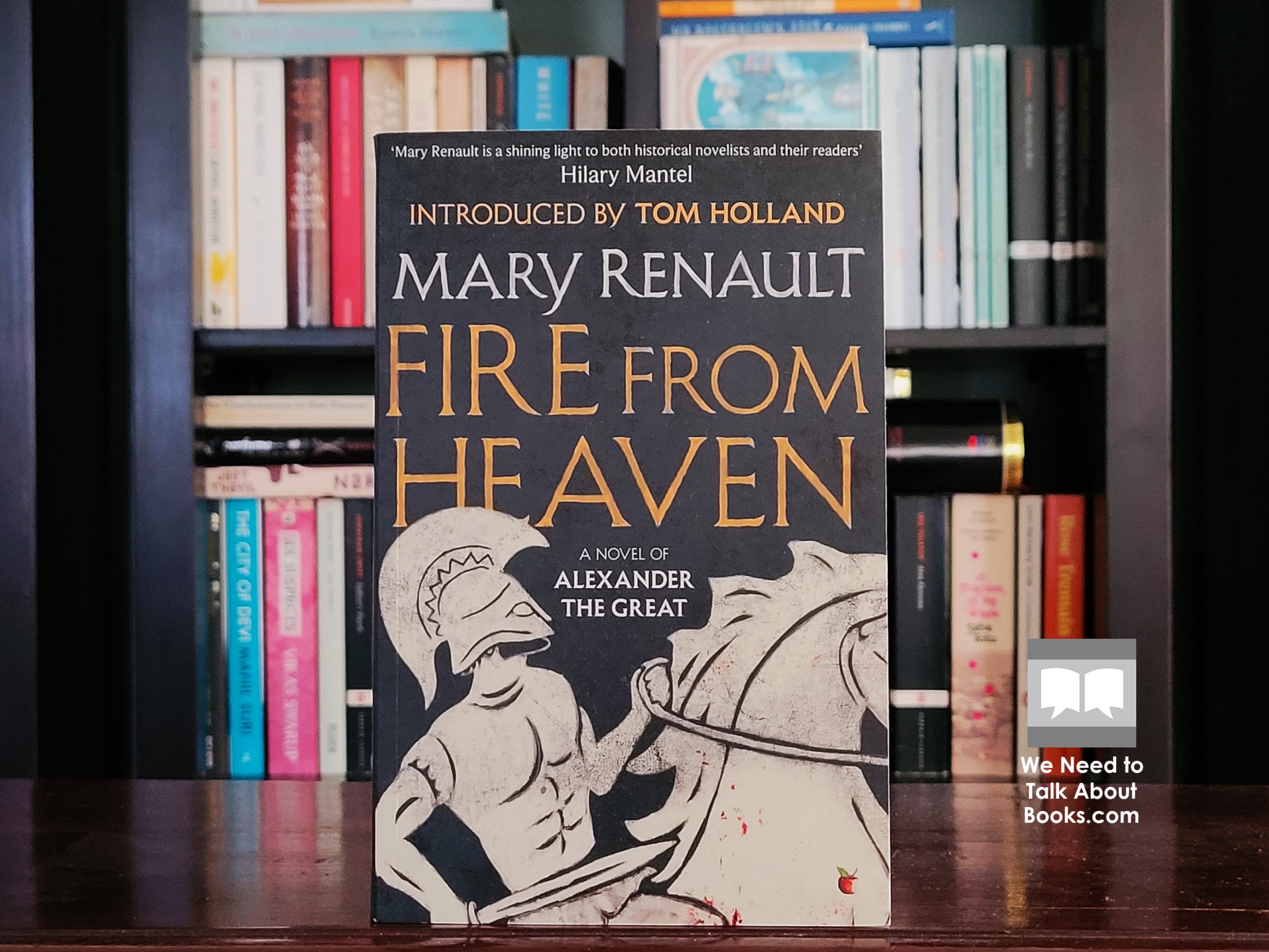

Historian Tom Holland, author of Persian Fire among other books on the ancient world, wrote the Introduction to this edition of the Alexander Trilogy. Calling Fire From Heaven “the greatest coming-of-age story ever to double as a work of historical fiction”, Holland suggests her attention to detail which adds so much colour to her novels sprung from an early interest in the artifacts from the period. That if she idealised Alexander it may have come out of identification with a child of an unhappy marriage, who escapes by throwing themselves into their work and finds happiness with a same-sex companion.

On the mixing of historical fact with fiction. Holland reminds us of the ambition of what Renault is attempting in Fire From Heaven – the telling of the childhood of a historical person; a subject largely overlooked by ancient biographers. That while “Renault could draw on a knowledge of antiquity capable of satisfying even the sternest classicist”, this would be insufficient for a story that aims to explain how the man Alexander sprung from the boy.

Philip’s telling Alexander he should be ashamed to sing so well – presumably in public, since it was recorded – is from Plutarch, who says the boy never played again. The tribal skirmish after is invented; we do not know where or when Alexander first tasted war. It can only be back-dated from his regency. At sixteen, he was trusted by the first general in Greece with a command of vital strategic importance, in the full expectation that experienced troops would follow him. By then they must have known him well.

From the Author’s Note

In this ambitious goal, I feel Renault succeeded. It is actually what Renault does best in Fire From Heaven. She shows Alexander going through experiences, learning the lessons that made him who he became. Reading it, I likened it to Aesop crossed with Sun Tzu. It was deliberate without feeling forced; surprising without being convoluted. Often it was just great writing.

The peaks stood dark against the sky, in whose deeps the stars were paling. The boy, holding his bridle and his javelin, watched for the first rows of dawn; he might be seeing at once for all. This he had known; for the first time, now, he felt it. All his life he had been hearing news of violent death; now his body told back the tale to him; the grinding of the iron into ones vitals, the mortal pain, the dark shades waiting as one was torn forth to leave the light, forever, forever. His guardian had left his side. In his silent heart he turned to Herakles, saying,’ why have you forsaken me?’

Dawn touched the highest peak in a glow like flame. He had been perfectly alone; so the voice of Herakles, still as it was, reached him unhindered. It said, ‘I left you to make you understand my mystery. Do not believe that others will die, not you; it is not for that that I am your friend. By laying myself on the pyre I became divine. I have wrestled with Thanatos knee to knee, and I know how death is vanquished. Man’s immortality is not to live forever; for that wish is born of fear. Each moment free from fear makes a man immortal.’

Besides the coming-of-age of the main character, there is much else in Fire From Heaven for readers to turn to in search for deeper meaning. There is Alexander’s friendships with those who would become his generals, such as Ptolemy. There is his relationship with Hephaistion, which both the characters and readers are conscious of as an of echoing Achilles and Patroclus.

The leaf sat in Hephaistion’s hand, about the size of a real one. Like a real one it was trembling; Quickly he shut his fingers on it. He felt now the full horror of the climb, the tiny mosaic of great flagstones far below, his loneliness at the climax. He had gone up in a fierce resolve to face, if it killed him, whatever ordeal Alexander should set to test him. Only now, with the gilt-bronze edges biting his palm, he saw that the test had not been for him. He was the witness. He had been taken up there to hold in his hand the life of Alexander, who had been asked if he meant what he had said. It was his pledge of friendship.

As they climbed down through the tall walnut tree, have Hephaistion called to mind the tale of Semele, beloved of Zeus. He had come in a human shape, but that was not enough for her; she had demanded the embrace of his divine epiphany. It had been too much, and she had burned to ashes. He would need to prepare himself for the touch of fire.

And there is also the role of Aristotle as tutor to Alexander and his entourage.

Two generations had seen each decent form of government decay into its own perversion: aristocracy into oligarchy, democracy to demagogy, kingship to tyranny. With mathematical progression, according to the number who shared the evil the deadweight against reform increased. To change a tyranny had lately been proved impossible. To change an oligarchy called for power and ruthlessness, destructive to the soul. To change a demagogy, one must become a demagogue and destroy one’s mind as well. But to reform a monarchy, one need only mould one man. The chance to be a king-shaper, the prize every philosopher prayed for, had fallen to him.

But the highlight for me was Alexander’s difficult relationship with his father, King Phillip II. Clearly having much in common, there were some nice bonding moments between father and son in the novel. But undoing much of that and driving a wedge between them was Phillip’s infidelities and sexual promiscuity.

‘All this happened because my father couldn’t be continent, even for decency in his own house. He’s always been the same. It’s known everywhere. People who should be respecting him, because he can beat them in battle, mock him behind his back. I couldn’t bear my life, to know they talked like that of me. To know one’s not master of oneself.’

‘People will never talk like that about you.’

‘I’ll never love anyone I’m ashamed of, that I know.’

Phillip defends his behaviour as necessary for a king as marriages help cement new alliances across his growing empire and sons provide new heirs should any fall short. But Alexander is sickened by it and even driven to hatred by the impact it has on his mother to the extent that he often takes her side and may not be fully cognizant of her own nefarious activities.

‘Alexander. Your father wants you back. I know it. You should believe me. I’ve known it all along.’

‘Good. Then he can do right by my mother.’

‘No, not only for the war in Asia. You don’t want to hear this, but he loves you. You may not like the way it takes him. The gods have many faces, Euripides says.’

Despite all the strengths of Fire From Heaven, I still feel the novel was lacking something. It does not follow the typical story arc of a coming-of-age story. Though he learns much in the course of the story, the Alexander of the novel is already quite independent, even wise from an early age. He already has his own ideas of who he wants to be, how he would do things differently and then it is a matter of proving that to himself even more than to his father. I did not necessarily discern a loss of innocence or a moment of understanding and clarity that marks a turning point in his life.

Instead, in a subtle inversion of the traditional coming-of-age tale, it is Alexander’s parents who are the immature, incomplete characters. It is they who need a transformation that may never come. While Alexander must discern what to take and what to leave from their example and influence.

First published in 1970, Fire From Heaven was shortlisted for the Lost Man Booker in 2010 – a one-off prize to recognise books that narrowly missed out on contention for the Booker Prize at the prize’s inception. As always, whenever I embark on a book series, I reserve judgement until I have completed the set. But Fire From Heaven marks a promising beginning. It is a must-read for those who have enjoyed her other historical novels and exemplifies the strengths that make her work a high standard for the genre.