For a short novel, Mister Pip delivers considerable emotional impact. A sad, beautiful story of loyalty and betrayal, set amongst an ignored and forgotten recent civil war, and an affirmation of the power of storytelling as a young girl’s imagination and hope is inspired by hearing Great Expectations read to her.

When a civil war between Papua New Guinea ‘Redskins’ and rebels fighting for independence commences on the island of Bougainville, everyone who can leave quickly does so. Those who are left behind struggle to maintain their simple village existence in the crossfire, their village repeatedly raided by Papuan and rebel fighters in turn.

Among them is the thirteen year old girl, Matilda, who wants for little more than a return to normality especially once her school closes due to the lack of any teachers. Matilda’s father has long since left for Australia in search of employment and Matilda was due to join him there with her mother before the escalating fighting made that impossible. The break of routine and the uncertainty of their future has made it difficult for anyone to ignore the dangerous situation they are all trapped in. But the ability to find escapism and relief in the imagination comes from an unlikely source who volunteers to reopen the school and teach the children.

His name was Mr Watts but the villagers called him ‘Pop Eye’ for the way his large eyes bulged out of his head. “He looked like someone who had seen or known great suffering and hadn’t been able to forget it”. Mr Watts is now the last white man on the island, but had long been a source of fascination for the locals. Particularly for the way he dressed in a white linen suit and a red clown nose while he pulled his wife Grace, a local woman, around on a trolley while she held a blue parasol above her head.

A big man with a small voice, Mr Watts tells the schoolchildren he wants their schoolroom to be ‘a place of light. No matter what happens’. Words that bear upon the children the reality of their predicament as they had never thought of their future as being uncertain. To teach them, Mr Watts produces a book that he declares to be ‘the greatest novel by the greatest English writer of the nineteenth century’; Great Expectations by Charles Dickens.

Through being read to by Mr Watts, the children enjoy their first imaginative experience; the ability of stories to transport us in space and time. They can escape the violence and uncertainty of their present lives to Victorian England, to get to know Pip, to make new friends and live vicariously. Each night the children retell the days reading to their equally engrossed families. Pip and his life become increasingly real for them.

No one has taken Pip to heart more than Matilda. She too knows about death and having an absent father. Like Pip she will also soon know about betrayal and loyalty. She wonders what Pip’s life has to teach her, how they may be kindred spirits. Down by the beach, she builds a little shrine to her fictional friend, decorated with sea shells. Her mother, Dolores, though, is untrusting of Mr Watts and the stories he plies the children with. A hardworking mother, she questions the educational value of stories over real-life skills and as a zealous Christian she is contemptuous of fiction over the truth and moral instruction of scripture. She is confounded that Mr Watts’ will believe in a fictional character like Pip, but not in the devil. She sees Mr Watts and his stories as a subversive, godless, influence on the children, yet she too is engrossed with the story of Pip.

The people of this small village are increasingly exposed to the brutality of the war around them as men and animals are slaughtered. Rumours of reprisals against those who have sided with the rebels reach the village. The social norms of the village begin to break down and people are praying more. They assume the outside world knows of their plight and is coming to help. Matilda draws further into the world of Dickens as she wonders about her father and whether she will have to choose between her mother’s world and Mr Watts’. She wonders if like Miss Havisham, her mother is embittered by disappointment and cannot move on. Although, as Great Expectations progresses, she also wonders about Pip’s choices once he has greater freedom and the ending leaves her confused.

When soldiers come to village, they spot the shrine to Pip on the beach. A misunderstanding leads to their leader believing Pip to be a real person, a spy for the rebels, and Mr Watts is brought forward to face their guns…

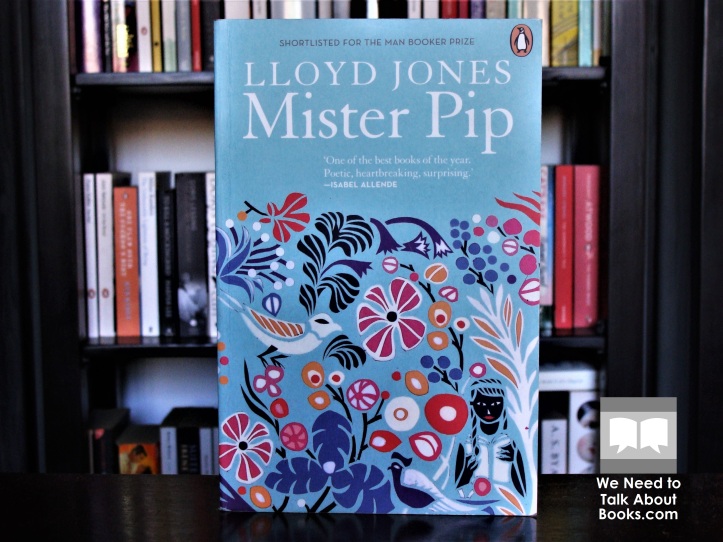

Mister Pip was highly praised when published and sold strongly. It won author Lloyd Jones the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best Book in 2007, was shortlisted for the 2007 Booker Prize and was regarded by some to be a favourite to win but lost to Anne Enright’s The Gathering. The film adaptation, starring Hugh Laurie as Mr Watts, opened late last year.

At only 220 sparse pages, Mister Pip is a short novel, but it packs considerable emotional punch. In fact I could barely scratch the surface of the events of the novel in writing the above as the action comes thick and fast. I was reminded when reading this novel of Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory. In the three Hemingway novels I’ve read, I’ve never been convinced that he pulled it off, but in Mister Pip Lloyd Jones makes it work. There is so much left beneath the surface but this does nothing to diminish the tragedy the reader will experience.

As well as scoring emotional hits, Mister Pip’s thematic range is large compared to the size of the novel. The power and importance of storytelling as humanising is an obvious theme and perhaps the one readers will most enjoy. But colonial and post-colonial themes are perhaps the strongest ones to voice themselves in the novel. Jones has said in interviews that he would describe this novel as a political book. The rebels fight for self-determination is being destroyed by the arrival of an invader to quash them. Matilda’s father left the island a while ago to seek employment in Australia, an experience that inevitably changes him. Grace, Mr Watts’ wife, was herself an islander who returned deeply altered by the outside world.

Still felt are the effects of previous visitors to the island. The missionaries who gave the islanders their unquestioned faith, as Dolores holds, which battles with a more secular view, such as Mr Watts’, for the heart and mind of Matilda. Also remembered is the copper mine, now closed, which was polluting, yet the villagers miss the opportunity to work and the income it provided.

Like his character Mr Watts, Jones’ affinity for Great Expectations comes from his interpretation of it as an emigrant story – the idea of home, the search for a new home once the old become untenable and the possibility, or otherwise, of ever returning. These are also concerns for Matilda in Mister Pip. Also like Pip in Great Expectations, Matilda will witness loyalty and betrayal, heroism and vengeance, and will be surprised and confused by the truth she discovers about the people closest to her.

It is also impossible not to mention the evocation in this novel of a brutal civil war in our recent history. Any details of the history of the conflict or the battling interests are absent from the novel. Suggestions have been made to Jones that explanatory notes should be included to inform readers. But perhaps this is something best left for the readers to investigate themselves as the lack of information is perhaps fitting for a conflict that, by Australian government estimates, took 15,000-20,000 lives, was the worst conflict in the Pacific since the Second World War, and yet was barely noticed by the rest of the world at the time and the ignorance of which continues to endure.

Jones wrote and rewrote Mister Pip eleven times, changing the focus, tone and setting of the novel several times. The finished work bears very few scars from such a difficult creation and is instead a read that is short and light in form but heavy and hard in substance. It strongly deserves to be read and dwelt over like the power of storytelling it extols and not ignored and forgotten like the civil war it is set against.

PS – with regards to the reference to Papuan’s as ‘Redskins’, especially in light of certain controversial American Football team nickname, a quote from author Lloyd Jones may help: “The skin colour of people from Bougainville is very black. By contrast, the Papuans’ skin colour has a red quality. People from PNG are routinely referred to as Redskins by the Bougainvilleans.”

Reblogged this on Sophie's blog….

LikeLike

Great review, I’ve been wanting to read this for some time but had forgotten about it. Will push it up my list! (Please consider checking out my blog! http://bookaweekblog.wordpress.com/)

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment! Mister Pip is definitely worth checking out, it has a lot going for it for a short book (I’m following your blog)

LikeLike

Thank you! Looking forward to seeing your reviews and hearing what you think of mine.

LikeLike

[…] been thinking a lot recently about how an author can use the plot to solve an issue of the format. Mister Pip recently brought this to my mind. Mister Pip is written from the point of view of a fourteen year […]

LikeLike

That sounds like a really interesting book. I read a previous novel by the author about the life of the doppelganger of Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha, and it showed the same qualities you mention regarding this book in your blog post. This book is also very interesting regarding the subject matter, because this conflict is quite unknown in the rest of the world, as is the conflict in (West-)Papua or in Maluku (both in indonesia). I lived a few years in Indonesia and got really interested in the history of this region and good literature is always the perfect starting point for some more “serious” reading on history and politics. By coincidence I have recently read two novels that are set in the region, F. Springer’s Bougainville and Christian Kracht’s Imperium (the latter is translated in English).

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. The movie is not bad either, it has Hugh Laurie and probably shows the role of mining interests in the conflict more than the novel

LikeLike

[…] Fernandes blogged about “Mr Pip” in 2014 and gives a detailed summary of the book. New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin’s review in […]

LikeLike