Wild Swans is, simply put, a masterpiece. It is a memoir of three generations of author Jung Chang’s family, principally told around the lives of her grandmother, mother and herself. Though I could not find confirmation, it is by some accounts the highest-selling memoir of all time with sales variously reported as being between 10-15 million copies. Despite this, it remains banned in China.

As appealing as a remarkable family story is, what makes Wild Swans important is that it serves as a microcosm for some of the twentieth century’s biggest events. The lives of these three women, of three successive generations, became entwined with these events. Through them we have a front row seat to the events and can appreciate them, understand what they meant, at a very personal level.

Chang’s grandmother, Yu-fang, was born into a China in turmoil. China’s isolationism, its Confucianist bureaucracy, which had kept it relatively safe and stable for centuries, was crumbling. The Emperor was overthrown and a fragile republic formed. China faced invasion by Japan, and possibly Russia, as well as growing internal conflict between rival warlords. It was to the general of one of these warlords, influential enough to play a role in the overthrow of a Chinese President, that Yu-Fang was offered by her father as a concubine.

While she has a life of relative luxury, prolonged boredom and loneliness take a psychological toll. Though she has a daughter, the General is getting old and ill and, as a concubine, Yu-Fang has few rights and may lose her daughter and all financial support. Her only option appears to be a daring escape and a life on the run.

Chang’s mother, De-hong (‘De’ meaning ‘virtue’, ‘hong’ meaning ‘wild swan’), grew up in a China that was now controlled by a nationalist government fighting Japanese invasion and in a city (Jinzhou) that was Japanese-occupied. During one period following the end of the Second World War, Jinzhou, which was considered strategically important, changed hands three times in four months – from Japanese, to Russian, to Chinese Communist to the American-supported Kuomintang. While the others participated in looting and destruction, mass-rape and mass-executions; the Communists won over the populace by keeping the peace, dealing humanely, getting amenities working again and stabilising inflation.

It was outrage at the injustice and prejudice towards women that drew Chang’s mother towards the Communists. She began harbouring communists, handing out leaflets, organising protests, all at great personal risk. De-hong would go on to marry a communist, Wang Yu. She knew him by repute as ‘wanted’ posters of him were hard to avoid. With complementary worldviews, strong mutual respect and admiration, it was not surprising they would fall in love not long after they met.

While, this book provides an insight into the lives of ordinary Chinese people in this period, it becomes difficult to view this family as anything but ordinary. Each generation possesses remarkable intelligence, strength of will, emotional fortitude and a strong work ethic. Such qualities in De-hong and Wang Yu meant they were inevitably given influential positions within the new communist government on merit. But the Communist Party would always view Chang’s mother with suspicion; coming from a city which was under Japanese and Kuomintang occupation for so long and where she was known to be politically active.

We don’t normally talk of non-fiction books having ‘themes’, but every author is probably going to be selective of which events to include and how to explain them and every reader is going to notice some patterns over others. Arguably, one such theme in Wild Swans is the conflict of interests that occur when people who are committed to a cause have relationships and families. Chang’s father, Wang Yu, was a deeply committed member of the Communist Party, to the extent that he frequently puts the party before his own family. I suppose a realist might argue that it is simply not possible to manage the two, and you either have to compromise or abandon one or the other. An idealist might argue that such conflicts are not natural consequences and that we should be able to pursue our convictions without such conflicts.

She did not blame the Party, or the revolution. Nor could she blame the women in the Federation, because they were her comrades and seemed to be the voice of the Party. Her resentment turned against my father. She felt that his loyalty was not primarily to her and that he always seemed to side with his comrades against her. She understood that it might be difficult for him to express his support in public, but she wanted it in private – and she did not get it. From the beginning of their marriage, there was a fundamental difference between my parents. My father’s devotion to communism was absolute: he felt he had to speak the same language in private, even to his wife, that he did in public. My mother was much more flexible; her commitment was tempered by both reason and emotion. She gave a space to the private; my father did not.

But it was not just Chang’s father who put the party first. De-hong would also put other interests before her children, much to her regret.

In the second half of the book, Mao looms large. Though, for a time, they lived a life or relative privilege, due to Wang Yu’s high rank, the growing influence of Mao in post-revolution China would bring devastation, depression and disillusionment. As Chang chronicles the impact of the Great Leap Forward, the process of Mao’s deification and the Cultural Revolution, she takes breaks from the story of her family to explain what was happening in China at large. She describes an era of mass delusion, self-censorship and a fear of thinking in case one accidently says the wrong thing, combined with feelings of intense national pride, unity and peace.

Under a dictatorship like Mao’s, where information was withheld and fabricated, it was very difficult for ordinary people to have confidence in their own experience or knowledge. Not to mention that they were now facing a national tidal wave of fervour which promised to swamp any individual coolheadedness. It was easy to start ignoring reality and simply put one’s faith in Mao. To go along with the frenzy was by far the easiest course. To pause and think and be circumspect meant trouble.

The last third of the book mostly concerns the youth of author Jung Chang (Er-hong, ‘second wild swan’) and the lives of her parents and siblings during the second-half of the Cultural Revolution. Chang, like most Chinese of her generation, grew up indoctrinated in the personality cult and deification of Mao. In fact, if we are saying a memoir can have themes, the theme of this last third of the book is of the author’s relationship with Mao.

Like many others, she was not capable of consciously questioning Mao’s genius or benevolence or noticing his hypocrisy even as her own parents were denounced and put in labour camps. As a 13-year-old, she devoted herself to the cause of a worldwide revolution, so that the whole world might benefit from what Mao had achieved for China. As an older teen, she voluntarily becomes a Red Guard. Slowly, as Chang was able to educate herself, she found her scepticism growing but, like losing one’s faith, she clung on to Mao for as long as she could, until the rational part of her found it excruciating.

It was in this period that I started to realise that it was Mao who was really responsible for the Cultural Revolution. But I still did not condemn him explicitly, even in my own mind. It was so difficult to destroy a god!

What I found most noticeable about this book was its style, or rather, its lack of any. I don’t mean this as a criticism. Chang writes very matter-of-factly about the events of her family history with no embellishment or poetry. I also found her very guarded about sharing anyone’s personal feelings, especially her own romantic ones, but perhaps that is a cultural difference. We can all think of memoirs and biographies that are lacking, precisely because they offer nothing more than a retelling of a series of events. So, it is difficult to put your finger on how Chang has managed to write an undeniably brilliant book with so little style. Perhaps, the events are so extraordinary, the story simply needs nothing additional. Or perhaps the styling is so subtle, and so well crafted, we hardly notice it.

All these misfortunes were told to me without much drama or emotion. Here it seemed that even shocking deaths were like a stone being dropped into a pond where the splash and the ripple closed over into stillness in no time.

And the events are extraordinary. To give one example, Chapter Seven shares the story of Chang’s mother’s ‘long march’; travelling a 1,000 mile journey to Sichuan mostly on foot. She endured immense pain and vomiting over dangerous terrain, with no help or sympathy and frequent criticism. Her husband was spared the toil due to his rank, but would not go out of his way to lessen hers. 700 miles on she endures military training and long lectures in unbearable heat, suffers a miscarriage and finds her normally indomitable will folding as she demands a divorce and wants out of the revolution. Travelling the final way by boat, she must survive the Yangtze gorges known as the ‘gates of hell’ on a small boat, avoiding numerous whirlpools, rapids and submerged rocks. At one point, they are fired upon by Kuomintang soldiers who strike the ammunition boat travelling with them. It explodes, narrowly taking them with it.

But just as a collision seemed inevitable, it floated past, missing them by inches. Nobody showed any signs of fear or elation. They all seemed to have grown numb to death.

For the reader this near-death experience, one of many, is stunning and you can almost visualise it in your mind. Yet, again, an incident such as this is told with little flourish and it does not even take up a whole page in an near-700 page book. The story has to move on.

Chang also shows awareness of her audience. An example would be how well she is able to explain why Chinese people supported various groups – whether Japanese, Kuomintang or Communists – at various times.

One day two peasants were killed by a rock slide. My father walked through the night along mountain paths to the scene of the accident. This was the first time in their lives the local peasants has set eyes on an official of my father’s rank, and they were moved to see that he was concerned about their well-being. In the past it had been assumed that all officials were only out to line their pockets. After what my father did, the locals thought the Communists were marvellous.

Following the death of Mao, China began a process of repairing the damage he had caused, a part of which meant greater openness to the outside world. This gave Jung Chang the opportunity to leave China to study abroad, becoming the first person from the People’s Republic of China to earn a doctorate from a British university.

Following the death of Mao, China began a process of repairing the damage he had caused, a part of which meant greater openness to the outside world. This gave Jung Chang the opportunity to leave China to study abroad, becoming the first person from the People’s Republic of China to earn a doctorate from a British university.

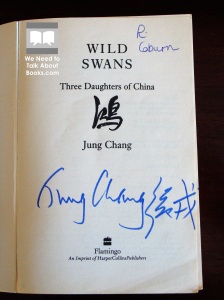

I had the pleasure of meeting Jung Chang, listening to her speak and having some books signed, when she toured Australia a few years ago. Though I had been aware of Wild Swans for a long time, the reason I finally got around to reading it now is because I want to get on to her second book Mao; The Unknown Story. Hearing about the evolution of her own thoughts towards Mao in Wild Swans only increased my desire to read it. Whatever my impressions of her second book may be when I read it, Wild Swans will certainly make a shortlist for choosing my favourite non-fiction book.

Excellent review of a superb novel. You;ve made me want to read this again. It had a huge impact on me when I read it the year it came out – until then my knowledge of chinese history was minimal. reading this book made me so angry at times (for example when the people are told to pull up every blade of grass, or to hand over all their iron ware even their cooking pots). Since then I’ve had the privilege of visiting China several times and the change that has happened in that country is nothing short of phenomenal. But you wont get people talking about the past – they are focused on the future

LikeLike

Thanks! I really appreciate that. Some of this book made me angry too, especially the destruction of all their material culture, which is trivial next to the loss of life. My knowledge of China is just starting to grow but I have a lot of books on China nearing the top of my TBR piles. I am a bit jealous that you’ve been able to visit China more than once!

LikeLike

I was fortunate in having a job which enabled me to travel

LikeLike

Sept 28, 2022–. I just started reading Wild Swans and came across your review of it. Thanks. It’s been on my book shelf forever, and what got me to pick it up was the book I’d just finished reading: “Peking Story,” by David Kidd. It’s much shorter, more tightly focused, but parallels Wild Swans’ focal quality on a very interesting family during historians changes taking place rapidly (1948-1952) in China. I highly recommend Kidd’s book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I will have to check it out

LikeLike