In Sugar Street, the final novel of Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo Trilogy, change and tragedy continue for both the al-Jawad family and for Egypt as the height of the Great Depression gives way to a new European war and the terror of new weapons while independence for Egypt remains elusive.

Note – since this novel is the third part of a trilogy, this review contains spoilers with regards to the first two novels; Palace Walk and Palace of Desire.

The al-Jawad family patriarch, Al-Sayyid Ahmad, and his friends are now paying the price for their years of heavy partying with hypertension and heart disease. Al-Sayyid Ahmad can no longer manage to ascend the stairs to the top floor of his own house. His wife, Amina, enjoying the greatest freedom of her life, does little more than pray and visit mosques. Their daughter, Aisha, formerly a great beauty, is now little more than a ghost; permanently grieving for the swift loss of her husband and sons to typhus.

Kamal left the room with a heavy heart. It was sad to watch a family age. It was hard to see his father, who had been so forceful and mighty, grow weak. His mother was wasting away and disappearing into old age. He was having to witness Aisha’s disintegration and downfall. The atmosphere of the house was charged with warning signs of misery and death.

Kamal, Al-Sayyid Ahmad and Amina’s youngest son and the focus of the previous novel Palace of Desire, has made the top floor of his parent’s house his personal apartment. Having suffered the torment of youthful unrequited love and the departure of his cultured friends, Kamal lives a steady monotonous existence. Now a respected school teacher, Kamal chooses to find intellectual stimulation in books rather than from friends. Darwin, Russell, Bergeson, Spinoza, Leibniz and Schopenhauer are his friends now. Release comes from writing philosophical articles for a small magazine while he denies himself any opportunity for love; relieving his natural compulsions as a regular client to a discrete prostitute.

You shrug off commitments so that nothing will distract you from your search for the truth, but truth lies in these commitments. You won’t learn about life in a library.

Kamal’s role is smaller in Sugar Street than in Palace of Desire but he continues to be burdened with his existential troubles.

The intellect can rob a person of peace of mind. An intellectual loves truth, desires honour, aims for tolerance, collides with doubt, and suffers from a continuous struggle with instincts and passions.

Change though, is coming for Kamal. A new friend provides the companionship and challenges to his intellect he has been missing while the prospect of a new romantic interest makes him realise how unprepared he is for such an opportunity.

Yasin, Kamal’s older half-brother is still around and, surprising to readers of the first two novels, he is still married to the same woman! As with Kamal, both Yasin and his father have only small roles in Sugar Street. The focus of the story moves on to the third generation of the al-Jawad family and Al-Sayyid Ahmad’s three very different grandsons.

Sugar Street, or al-Sukkariya, is the street in Cairo where Al-Sayyid Ahmad’s daughter, Khadija, lives with her husband Ibrahim Shawkat and sons Abd al-Muni’m and Ahmad. Bold and headstrong, both young men have no qualms about defying their parents unlike the previous generation.

We rear our children, guide them, and advise them but each child finds his way to a library, which is a world totally independent of us. There total strangers compete with us. So what can we do?

Though their personalities have much in common, their politics could not be more different. Abd, a young man of strong religious convictions, has joined the Muslim Brethren and is becoming increasingly radicalised. Ahmad though, is an equally committed communist who sees his brother’s and his family’s traditions and beliefs as backward.

In his powerful voice, Abd al-Muni’m said, “We’re not merely an organisation dedicated to teaching and preaching. We attempt to understand Islam as God intended it to be: a religion, a way of life, a code of law, and a political system.”

“Is talk like this appropriate for the twentieth century?”

The forceful voice answered, “And for the hundred and twentieth century too.”

“Confronted by democracy, Fascism and Communism, we’re dumbfounded. Then there’s this new calamity.”

Abd al-Muni’m asked his brother, Ahmad, “What knowledge of yours lets you blather on so?”

Ahmad answered calmly, “I know it’s a religion, and that’s enough for me. I don’t believe in religions.”

Abd al-Muni’m asked disapprovingly, “Do you have some proof that all religions are false?”

“Do you have any proof they are true?”

But while the Shawkat brothers are openly defiant in their beliefs and the political aims of their respective causes are openly radical, their cousin Ridwan, the son of Yasin and his first wife, has opted for a more conventional political career yet he is hiding the most shocking secret of all. Ridwan, who has inherited the handsome features of his father and grandfather and knows it as well, understands the corrupt game of high-powered connections that is conventional politics and has begun his ascent to power by having a homosexual affair with a prominent politician!

The reaction to this fierce quarrel was universal silence, which pleased Ridwan. His eyes roamed around, following some kites than circled overhead or gazing at the groups of palm trees. Everyone else felt free to express his opinion, even if it attacked his Creator. Yet he was compelled to conceal the controversies raging in his own soul, where they would remain a terrifying secret that threatened him. He might as well have been a scapegoat or an alien. Who had divided human behaviour into normal and deviant? How can an adversary also serve as judge?

Sugar Street is set roughly between 1934 and 1945. So it begins with the hardship and uncertainty of the Great Depression, the looming threat of a new European war and with the British desiring neither to stay in Egypt nor to end the protectorate and grant independence. In shades of the first novel, Palace Walk, British soldiers still open fire on protesting students but full independence for Egypt remains frustratingly remote. That frustration and uncertainty is best exemplified by Al-Sayyid Ahmad’s three rebellious grandsons; their rejection of previously assured careers for divergent paths towards self-actualisation and political power.

Once the war begins, the frequent threat of air raids terrorise the people of Cairo. Both the al-Jawad family and Egypt experience unexpected tragedy and inevitable change with such force and speed that they can barely survive it.

I do not wish to say anything more about Sugar Street. Now that I have finished the trilogy it is time to reflect on it as a whole.

There is much I would like to write about but alas I am unqualified to do so! For instance, it is often said that Mahfouz’s writing is infused with traditional Egyptian storytelling techniques – something I can’t claim to know anything about. The novel is also infused with quotes from the Qur’an, Arabic poets and pop songs. One technical aspect I did notice was that, unlike almost every contemporary writer in English, there is practically no foreshadowing. The advantage of this is that events in the story, when they occur, are often surprising, even shocking. The downside is that you don’t have that obvious inducement to keep the pages turning and instead wonder where the story is going and whether you are still interested. It makes you realise what a cheap but effective trick foreshadowing is.

Something that is also frequently mentioned about Mahfouz is that he has been influenced by French and existentialist writers – Camus, Flaubert, Zola and especially, Proust. Since I am not overly familiar with these writers I can’t say much about this influence and I could not sense much of their influence in Palace Walk. Their influence becomes far more apparent in the following two novels of the trilogy.

The style of the writing therefore changes through the trilogy. Palace Walk is very much about the dictatorial rule of family patriarch Al-Sayyid Ahmad, the two sides of his character and of Cairo. Mahfouz’s blunt evocation of the oppressed existence of his family is confronting to the reader. Palace of Desire has less dialogue, a slower plot and is focused on Kamal and his introspective monologues. Easily the most ‘Westernised’ character of the trilogy, Kamal’s existential dilemmas as he struggles with unrequited love, loss of faith and abandonment of tradition make him the most interesting and relatable character, arguable the trilogy’s central character. Though this introspection continues into Sugar Street, by now the reader is invested in the al-Jawad family and is most interested in learning their fate.

An aspect I find interesting, but am also unable to answer, is the meaning of the setting compared with the timing of the writing. The trilogy is set roughly between 1917 and 1945, but it was published in 1956, in other words, shortly after the 1952 revolution. Given that it is a story of life in a strict, traditional and, even for its time, old-fashioned family; is the novel commenting on what life was like in the not too distant past? On how Egyptian society has changed in the interim? Are there inferences to the 1952 revolution contained in the evocation of the stages that came before it? I cannot say but would like to know. Equally, given recent events in Egypt, I wonder if the novels have found a new resonance.

Five years ago, hundreds of young protestors were killed when demonstrating against the thirty year Mubarak dictatorship. Since then, a short-lived elected government has been overthrown and replaced by the rule of General Abdel-fattah al-Sisi. Today, Egyptians are forbidden to protest and even minor expressions of dissent can result in arrest without charge and imprisonment without trial.

The trilogy is heavily political, but, while that may prevent you from gaining a full understanding of the author’s message, it should not detract from everything else there is to enjoy in these works – the complex characters, the exotic setting and the tragic plot.

I have previously enjoyed multi-generational family sagas, such as Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children and The Moor’s Last Sigh and Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex. With the private battles of wills between fathers and son, husbands and wives and how fates can be sealed by choices made by previous generations. Against this, the small scale of the personal story of otherwise ordinary families is put into context as they are swept along by massive social upheaval – war, disease, revolution. If you enjoy such sagas too, you will find much to enjoy in the Cairo Trilogy.

As the country changes rapidly, each generation of men in the al-Jawad family rebel against the ideals of the previous generation, choosing alternative careers, lifestyles, politics and beliefs. Change does not come for the women of the family though, who continue to be denied education and employment and serve as little more than domestic servants and property to be transferred by marriage.

The insight into another time and another culture is also a highlight of the trilogy and one full of surprises. Though we are following a very traditional, conservative and religious family, in a relatively conservative country; the novels lift the veil on an underground Cairo of alcohol consumption, drug use, adultery and prostitution. At no time do I sense the author making any judgement on the traditions, beliefs, or politics of his characters or the choices they make with regards to marriage, sex or drinking. Such interpretations are left for the reader to make.

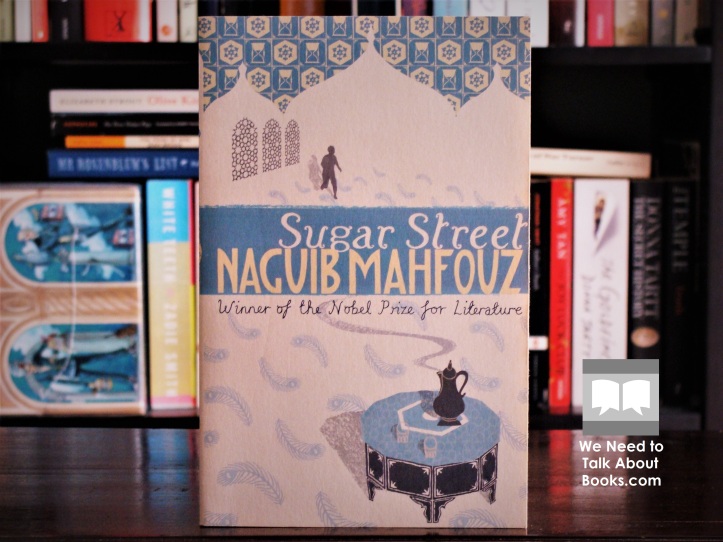

On final thing I want to say – the publisher, Black Swan, has done a wonderful job with the cover designs for these books. I remember first spotting Palace Walk at an independent book store and eagerly inquiring whether it would be possible to get a matching set for the trilogy. I am glad I did, they are very pretty. Although I do think the blurb for Palace of Desire contains a spoiler.

Mahfouz is still the only Arabic writer to have won a Nobel Prize for Literature. For English readers the Cairo Trilogy, considered his masterpiece, is probably the best opportunity to experience his writing. Readers will be plunged into a world that may seem exotic and alien in the extreme, but one that is not as far removed from our own past as we may think and one we can benefit from by experiencing it through literature.

For my reviews of the other novels of the Cairo Trilogy, see here.

[…] See me review of the second book in the Cairo Trilogy, Palace of Desire, and the third, Sugar Street. […]

LikeLike

[…] ← Book Review: Palace Walk Book Review: Sugar Street → […]

LikeLike

Do you know how the trilogy was received in Egypt when it was published? Salman Rushdie had a lot of, erm, trouble when he wrote books that upset the government. Did the Egyptian government say anything about the prostitution, etc from this trilogy?

LikeLike

As far as I am aware, Mahfouz received no backlash from the contents of the Cairo Trilogy. I think they have even been made into films (though probably less explicit than the books). He did get considerable backlash for his next book, The Children of Gebelawi, which I think portrayed Muslim prophets as secular people fighting for social change. There were protests, calls for it to be banned and for Mahfouz to be charged with blasphemy, and he even survived an assassination attempt. When Rushdie received his fatwa, there were some Muslims who argued that Mahfouz deserved one too. Mahfouz was against Rushdies fatwa but said he did not mind if people boycotted the book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That last part is a good point: people don’t have to read anything, but it’s ludicrous to demand someone’s head for the book’s existence!

LikeLike

I must re-read this trilogy, it’s been years but I remember loving them. My set are different copies to yours, with vintage-style illustrations on the cover, they’re quite lovely. It’s interesting what you say about foreshadowing, as a device often used in western writing. I suppose the idea with this trilogy was that you would become so immersed in the multi-generational family story that you would read on because you care about the characters. Which I did. I don’t have any other books by Mahfouz, have you read The Children of Gebelawi? If so, would you recommend it?

LikeLike

I haven’t read The Children of Gebelawi, I only heard about it from learning about Mahfouz while reading the Cairo Trilogy. I think I would definitely be interested in it, but it is hard to say when I would be able to get around to it!

LikeLike

[…] See also my review for the third novel in the Cairo Trilogy, Sugar Street. […]

LikeLike

[…] See me review of the second book in the Cairo Trilogy, Palace of Desire, and the third, Sugar Street. […]

LikeLike

You state here that the reader will want to know how it continues; I am an exception.

I just finished Palace of Desire and it left me as a complete mess!

Like Kamal, I have no one to share the growing emotional turmoil. A sadness caused by love.

I love Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad. I can’t name it differentely. I was shocked by his predicament at the end of Palace of Desire, but I loved how much affection it all created with his family (father-childrens bonds have always been my weak spot) and most of all with his friends. The last is one of my all time favourite scenes!

Seeing him pushed back in Sugar Street in favour of his grandsons is one thing I could have lived with, if not for the fact that the author took all he ever was from him: his strength, his power, his health, not to speak about his son-in-law and two grandchildren and, as I spoiled myself, quite some of his friends who die before him…

It made me angry, of all things, that so soon after he recovers, all the attention is grabbed by Aisja’s family dying.

At least God should have let him go at the moment there was still room in the hearts from his family to mourn. Now those who are left are full of pain and sadness already and, as Kamal wonders at his sickbed, he might be forgotten way to soon.

For the first time in my life, I might not actually finish a series I started.

LikeLiked by 1 person